- Home

- My Story

- Current Issue

-

Past Issues

- Anniversary Edition (5 year)

- Bald Eagle >

- Climate Change

- Common Sense Advocacy

- Conversations on Conservation I

- Conversations on Conservation II

- Conversations on Conservation - Part III

- Conversations on Conservation: Part IV

- Conversations on Conservations: Part V

- Conversations on Conservation: Part VI

- Coral Reef >

- Ecology, Economics and Evolution

- Elephant

- Flying Fox

- Gopher Tortoise, Eastern Indigo Snake and Gopher Frog >

- Honeybee >

- Invasive Species

- Lion

- Monarch Butterfly

- Native Orchids >

- Pitcher Plant Moth, Happy-Face Spider & Ogre-Faced Spider

- Tiger >

- Water

- How can you help?

- More...

Photo credit: Marcus Chua (Photo used with permission)

In Spotlight: Flying Foxes

|

Join me on a virtual trip as we travel to Tioman Island, a tropical paradise 20 miles (32 km) off the southeastern coast of the Malaysian Peninsula. While this island may seem like the perfect vacation spot to us, to Dr. Sheema Abdul Aziz the island is her research site. Over the last four years, Dr. Sheema has been studying giant fruit bats also known as flying foxes. Her research is the first of its kind in Peninsular Malaysia, as it investigates the positive role flying foxes play in providing ecosystem services, while also addressing the human-bat conflict.

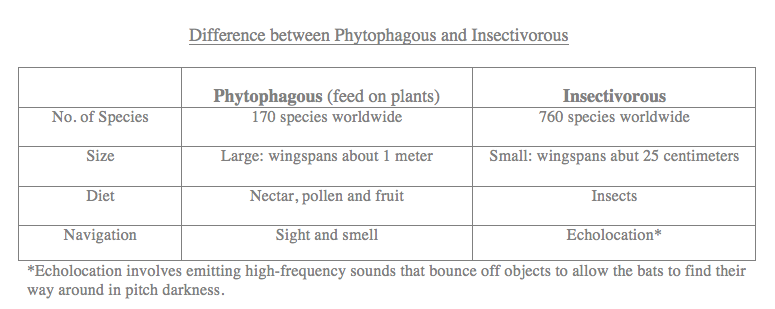

I had read about Dr. Sheema's work while researching the Malayan tiger in 2015. Her work had sparked my interest in bats and over the years I have frequented her website. In considering my next Edition I decided to reach out to her via email for an interview to which she kindly agreed. In this interview, Dr. Sheema gives us both an overview of her preliminary findings and a sneak peek into what is yet to come. The interview also covers a range of thought provoking information and possibly answers to questions you may have asked yourself about this species. I would like to thank Dr. Sheema for making time for this interview and for sharing her work and passion with us. Most people perceive bats as neither charismatic nor appealing; however, their importance cannot be overstated. There are over 900 species of bats, which make up ¼ of all mammals worldwide. Bats are the only know mammals capable of true flight. They are divided into the two main groups-phytophagous (feed on plants) and insectivorous. Phytophagous bats are known as fruit bats. There are close to 170 species of fruit bats and their diet mostly comprises of fruit, nectar and pollen. The remaining 760 species of bats fall under insectivorous bats and as their name suggests their diet comprises of insects. |

Finally, like me, if you have been wondering why bats hang upside down... the answer is, unlike birds their wings are not designed to launch them into flight from an upright position. Hence they hang upside down, which allows them to free-fall to gather momentum for flight.

In this interview, we focus on a subgroup of fruit bats called flying foxes, the largest bats in the world.

The interview has been edited.

In this interview, we focus on a subgroup of fruit bats called flying foxes, the largest bats in the world.

The interview has been edited.

Dr. Sheema Abdul Aziz

Field Biologist and Conservationist

Ayesha Siraj

Interviewer

Field Biologist and Conservationist

Ayesha Siraj

Interviewer

Ayesha: First and foremost, I would like to start by saying that I am very grateful for the work you do. Bats are critical to our ecosystems, but often they are not valued for their contribution and are generally misunderstood. Thank you for your dedication to the species and also for agreeing to do this interview. I really appreciate it.

Dr. Sheema: Thank you so much for your kind words and for highlighting my work. I really appreciate your support!

Ayesha: What got you interested in bats? What drew you to them, to study them, and to advocate for their conservation?

Dr. Sheema: I became interested in bats 13 years ago after being granted an HSBC-Earthwatch Fellowship to volunteer on a project studying insectivorous bats in Malaysia. That project was led by Dr. Tigga Kingston, who is now at Texas Tech University in the United States. At the time, I hadn't spared much thought to bats. I didn't think they were interesting or important in any way. Tigga's project completely changed the way I viewed bats. Holding a tiny little fluff ball with wings, and getting to see it up close and personal was a life-changing experience for me. I knew then that I wanted to study bats and help protect them.

This experience motivated me to do an MSc in Conservation Biology, where I got to analyse the data from Tigga's project. But, that project was only focused on insect-eating bats and at the time, there weren't many studies in Peninsular Malaysia focused on fruit bats. I started to wonder about this other, mysterious group of bats that have such a unique relationship with plants. (Fruit bats play an important role as seed dispersers and pollinators.) I became really excited when I found out that Malaysia has Pteropus spp, giant fruit bats also known as flying foxes! How cool is that? I couldn't believe that we knew so little about these animals since hardly anyone in the country was interested in studying them, or their ecological roles. Dr. Melvin Gumal of Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS ) Malaysia had studied flying fox ecology in Sarawak for his Ph.D (Gumal 2001), but when it comes to Peninsular Malaysia, most of the studies have focused on virology, parasitology, or genetics. Nobody was looking at how these bats fit into our ecosystem. There have only been two preliminary, one-off papers attempting to determine how severely they've been affected by hunting, deforestation, and conflict with humans (Mohd-Azlan et al. 2001; Epstein et al. 2009). Nothing long-term, and in Sabah no research has been done at all. Flying foxes are a completely overlooked animal group in Malaysia because most people don't think they're important in any way, and even conservationists and scientists have largely ignored them here.

On the other hand, I was completely fascinated by them. Flying foxes are such huge bats with incredible wingspans. Given that they can cross long distances in just one night I was convinced that they must play really important roles in shaping and maintaining tropical ecosystems. In fact, I believe flying foxes and other pollinating bats are not only critical to forest ecosystem, but they are probably important contributors in marine conservation too because they feed in mangroves. So, it is likely they help maintain the health of mangrove ecosystems as well. And you need healthy mangroves in order to have healthy coral reefs and fisheries. For these reasons, flying foxes are probably a super important keystone animal group for tropical ecosystems.

So surely, declines in flying fox numbers must have serious knock-on effects for plants, and the animals that depend on those plants for food. How can degraded forests recover if the animals that are crucial for healthy ecosystem functioning, such as flying foxes, are now missing from that area? However, most people in Malaysia don't realize all this, and we don't know what the specific effects of their declines might be. So, I decided that I needed to do something about that.

Ayesha: Why are they called flying foxes?

Dr. Sheema: They’re called flying foxes because they look like puppies with wings! Their heads and faces resemble foxes or dogs. They are quite adorable.

Ayesha: Are flying foxes endemic to Malaysia or found in other parts of the world as well? What is their range?

Dr. Sheema: There are many species of flying foxes globally; around 60 species or so at last count. They range from islands off the eastern coast of Africa all the way to the Pacific islands. But, it is important to note that they are found in tropical and subtropical regions within this area. Malaysia does not have any endemic species.

Ayesha: How are flying foxes different from other species of fruit bats? Are they certain traits that set them apart?

Dr. Sheema: The term ‘flying foxes’ refers to giant fruit bats. You may find that some researchers in other parts of the world use the term 'flying fox' to refer to all bats in the family Pteropodidae, Old World fruit bats, regardless of size. However, here in Southeast Asia, we generally use it as a specific term to refer only to the giant bats of the genera Pteropus and Acerodon – the largest bats in the world. In many Southeast Asian languages, we have a separate word for flying foxes that differentiates them from other bats. In the Malay language, flying foxes are called 'keluang' ('kalong' in Indonesia), whereas all other bats are 'kelawar' ('kelelawar' in Indonesia) - regardless of whether they're the smaller fruit bats or insectivorous bats. So, there is a very clear and definite linguistic distinction that’s been made here in the cultures of this region.

Ayesha: It's interesting how regional languages and culture have helped create a distinction between giant fruit bats and the other bats. So, would it be accurate to assume that the primary distinguishing feature between giant fruit bats (also known as flying foxes) and other fruit bats would be the size of the bats then?

Dr. Sheema: Yes, that’s correct. In Malaysia, the smaller fruit bats are grouped together with insect-eating bats under the same term – separate from the giant fruit bats. Some local communities however may have their own specific names for the small fruit bats that distinguish them from the insect-eating bats and the flying foxes.

Ayesha: What is their lifespan?

Dr. Sheema: We don’t know for sure how long flying foxes live in the wild. But, flying foxes in captivity have been known to live up to 30-40 years.

Ayesha: What is the gestation period for flying foxes and how many pups do they have annually?

Dr. Sheema: Flying foxes generally have only one pup a year and the gestation period is about six months.

Ayesha: Bats are nocturnal creatures. In the case of flying foxes, do they have highly evolved vision, or are there other senses they use to navigate through the darkness?

Dr. Sheema: Flying foxes definitely have good nocturnal vision, but they also have a highly developed sense of smell. This helps them locate fruits and flowers in the forest at night.

Ayesha: Are flying foxes solitary creatures or do they live in groups?

Dr. Sheema: Flying foxes roost gregariously, and are described as ‘colonial’, meaning that they roost together in large groups known as colonies.

Ayesha: What specific flying fox species do you study?

Dr. Sheema: I started out studying the island flying fox, Pteropus hypomelanus also known as the variable flying fox or small flying fox. But, I’m hoping to now expand my research to include other flying fox species and also other Old World fruit bats also known as pteropodid bats after their family name, Pteropodidae.

Ayesha: How long have you been studying the flying foxes? Does your research involve lab work, fieldwork or both?

Dr. Sheema: I only started studying flying foxes in 2014. This research involves a mixture of both fieldwork and lab work. The next phase of my work will involve mostly fieldwork.

Ayesha: Can you tell us about your study site and why did you choose this specific site and not another location in Malaysia? Where is it and how long have you been observing the flying foxes at this location?

Dr. Sheema: My field site is Tioman: a beautiful tropical island off the southeastern coast of Peninsular Malaysia. It’s about 32km from the mainland, located in the South China Sea. I chose this island for my research because it’s probably the last place in the entire country where you can see large colonies of flying foxes roosting permanently in easily accessible locations. I first observed flying foxes there when I visited in 2013 and the island officially became my research site in 2014.

Ayesha: What does their habitat look like on this particular island? Is proximity to food and water a factor for them in choosing a roosting site?

Dr. Sheema: It depends on what you mean by ‘habitat’! The flying foxes themselves roost right in the middle of villages – they live amongst humans! But, they appear to be feeding in a variety of different habitats all over the island –rainforest, mangroves, and in people’s orchards and back gardens. We’re not really sure at this point what exact factors influence their choice of roosting site. However, on Tioman we suspect that they roost in human areas because they feel no threat from the locals. That is because the local communities on the island are mostly ethnic Malays, who practice Islam. You may already know this, but Muslims don’t eat bats due to religious dietary restrictions and therefore they don’t hunt them.

Ayesha: While reading about your work I got the sense that one of the preliminary questions you focused in your research was what do flying foxes eat on Tioman Island? What were your findings?

Dr. Sheema: Yes – I had to start by answering that very basic question first, because as I have previously stated the research had never been done before, so we had no idea! I found that the number one favourite food that comprises the core diet of Tioman’s flying foxes is wild figs from the forest. However, when people’s mango trees are fruiting, mango fruits make up an important part of their diet too. We, also, have video footage proving that flying foxes feed on nectar from durian flowers. Our dietary analysis is still very preliminary though so I’m quite confident that in time if we improve our techniques and approach we’ll be able to identify more food plants that they feed on.

Ayesha: How do you find out what they eat?

Dr. Sheema: The easiest way to find out is to collect flying fox poop and analyse what’s in it. Traditionally, researchers have done this by using microscopes to identify seeds and pollen grains. But, it’s really tough to do this if you don’t have a reference collection to compare with! So, we tried a new approach using molecular analysis. We were successful in identifying plant DNA in the flying fox poop, which tells us what plants the flying foxes were feeding on. Another method that we’re hoping to test out in the future is satellite tracking – fixing the bats with collars containing satellite transmitters that will tell us where the bats go to forage.

Ayesha: You mentioned that you have video footage of flying foxes feeding on nectar from durian flower. Was installing camera traps in the durian tree part of the effort to learn about their diet?

Dr. Sheema: The camera traps in durian trees were not really a method to determine what the flying foxes were eating – we already knew they were feeding on durian flowers because we had identified durian pollen grains in the feces. The camera traps were to help us determine the feeding behaviour of flying foxes in the durian trees and to identify any other animal visitors along with their feeding behaviour too.

Ayesha: Given that the research that you are conducting on the flying foxes is our first glimpse into the lives of these creatures for the Malaysian Peninsula every new finding or observation must be exciting. With that in mind, I am curious to learn about what kind of behavior the camera traps revealed. Had you hypothesized something and were you proven right, or did the footage contradict your hypothesis?

Dr. Sheema: Well I didn’t really have a specific hypothesis. I wanted to use the camera traps to investigate whether the flying foxes were actually pollinating the durian flower. I wanted to believe that this was true because we had already discovered durian pollen in their droppings, but I was a bit skeptical about them being pollinators due to their large size. I was concerned that they might damage the flower in the process of feeding. But I was really blown away when I saw the video. There was irrefutable evidence that the flying foxes were indeed pollinating the durian flower! Despite their size they were not damaging the flowers. In fact, in some cases they were actually feeding quite delicately! I was also pleasantly surprised to learn how hardy and robust durian flowers really are!

Dr. Sheema: Thank you so much for your kind words and for highlighting my work. I really appreciate your support!

Ayesha: What got you interested in bats? What drew you to them, to study them, and to advocate for their conservation?

Dr. Sheema: I became interested in bats 13 years ago after being granted an HSBC-Earthwatch Fellowship to volunteer on a project studying insectivorous bats in Malaysia. That project was led by Dr. Tigga Kingston, who is now at Texas Tech University in the United States. At the time, I hadn't spared much thought to bats. I didn't think they were interesting or important in any way. Tigga's project completely changed the way I viewed bats. Holding a tiny little fluff ball with wings, and getting to see it up close and personal was a life-changing experience for me. I knew then that I wanted to study bats and help protect them.

This experience motivated me to do an MSc in Conservation Biology, where I got to analyse the data from Tigga's project. But, that project was only focused on insect-eating bats and at the time, there weren't many studies in Peninsular Malaysia focused on fruit bats. I started to wonder about this other, mysterious group of bats that have such a unique relationship with plants. (Fruit bats play an important role as seed dispersers and pollinators.) I became really excited when I found out that Malaysia has Pteropus spp, giant fruit bats also known as flying foxes! How cool is that? I couldn't believe that we knew so little about these animals since hardly anyone in the country was interested in studying them, or their ecological roles. Dr. Melvin Gumal of Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS ) Malaysia had studied flying fox ecology in Sarawak for his Ph.D (Gumal 2001), but when it comes to Peninsular Malaysia, most of the studies have focused on virology, parasitology, or genetics. Nobody was looking at how these bats fit into our ecosystem. There have only been two preliminary, one-off papers attempting to determine how severely they've been affected by hunting, deforestation, and conflict with humans (Mohd-Azlan et al. 2001; Epstein et al. 2009). Nothing long-term, and in Sabah no research has been done at all. Flying foxes are a completely overlooked animal group in Malaysia because most people don't think they're important in any way, and even conservationists and scientists have largely ignored them here.

On the other hand, I was completely fascinated by them. Flying foxes are such huge bats with incredible wingspans. Given that they can cross long distances in just one night I was convinced that they must play really important roles in shaping and maintaining tropical ecosystems. In fact, I believe flying foxes and other pollinating bats are not only critical to forest ecosystem, but they are probably important contributors in marine conservation too because they feed in mangroves. So, it is likely they help maintain the health of mangrove ecosystems as well. And you need healthy mangroves in order to have healthy coral reefs and fisheries. For these reasons, flying foxes are probably a super important keystone animal group for tropical ecosystems.

So surely, declines in flying fox numbers must have serious knock-on effects for plants, and the animals that depend on those plants for food. How can degraded forests recover if the animals that are crucial for healthy ecosystem functioning, such as flying foxes, are now missing from that area? However, most people in Malaysia don't realize all this, and we don't know what the specific effects of their declines might be. So, I decided that I needed to do something about that.

Ayesha: Why are they called flying foxes?

Dr. Sheema: They’re called flying foxes because they look like puppies with wings! Their heads and faces resemble foxes or dogs. They are quite adorable.

Ayesha: Are flying foxes endemic to Malaysia or found in other parts of the world as well? What is their range?

Dr. Sheema: There are many species of flying foxes globally; around 60 species or so at last count. They range from islands off the eastern coast of Africa all the way to the Pacific islands. But, it is important to note that they are found in tropical and subtropical regions within this area. Malaysia does not have any endemic species.

Ayesha: How are flying foxes different from other species of fruit bats? Are they certain traits that set them apart?

Dr. Sheema: The term ‘flying foxes’ refers to giant fruit bats. You may find that some researchers in other parts of the world use the term 'flying fox' to refer to all bats in the family Pteropodidae, Old World fruit bats, regardless of size. However, here in Southeast Asia, we generally use it as a specific term to refer only to the giant bats of the genera Pteropus and Acerodon – the largest bats in the world. In many Southeast Asian languages, we have a separate word for flying foxes that differentiates them from other bats. In the Malay language, flying foxes are called 'keluang' ('kalong' in Indonesia), whereas all other bats are 'kelawar' ('kelelawar' in Indonesia) - regardless of whether they're the smaller fruit bats or insectivorous bats. So, there is a very clear and definite linguistic distinction that’s been made here in the cultures of this region.

Ayesha: It's interesting how regional languages and culture have helped create a distinction between giant fruit bats and the other bats. So, would it be accurate to assume that the primary distinguishing feature between giant fruit bats (also known as flying foxes) and other fruit bats would be the size of the bats then?

Dr. Sheema: Yes, that’s correct. In Malaysia, the smaller fruit bats are grouped together with insect-eating bats under the same term – separate from the giant fruit bats. Some local communities however may have their own specific names for the small fruit bats that distinguish them from the insect-eating bats and the flying foxes.

Ayesha: What is their lifespan?

Dr. Sheema: We don’t know for sure how long flying foxes live in the wild. But, flying foxes in captivity have been known to live up to 30-40 years.

Ayesha: What is the gestation period for flying foxes and how many pups do they have annually?

Dr. Sheema: Flying foxes generally have only one pup a year and the gestation period is about six months.

Ayesha: Bats are nocturnal creatures. In the case of flying foxes, do they have highly evolved vision, or are there other senses they use to navigate through the darkness?

Dr. Sheema: Flying foxes definitely have good nocturnal vision, but they also have a highly developed sense of smell. This helps them locate fruits and flowers in the forest at night.

Ayesha: Are flying foxes solitary creatures or do they live in groups?

Dr. Sheema: Flying foxes roost gregariously, and are described as ‘colonial’, meaning that they roost together in large groups known as colonies.

Ayesha: What specific flying fox species do you study?

Dr. Sheema: I started out studying the island flying fox, Pteropus hypomelanus also known as the variable flying fox or small flying fox. But, I’m hoping to now expand my research to include other flying fox species and also other Old World fruit bats also known as pteropodid bats after their family name, Pteropodidae.

Ayesha: How long have you been studying the flying foxes? Does your research involve lab work, fieldwork or both?

Dr. Sheema: I only started studying flying foxes in 2014. This research involves a mixture of both fieldwork and lab work. The next phase of my work will involve mostly fieldwork.

Ayesha: Can you tell us about your study site and why did you choose this specific site and not another location in Malaysia? Where is it and how long have you been observing the flying foxes at this location?

Dr. Sheema: My field site is Tioman: a beautiful tropical island off the southeastern coast of Peninsular Malaysia. It’s about 32km from the mainland, located in the South China Sea. I chose this island for my research because it’s probably the last place in the entire country where you can see large colonies of flying foxes roosting permanently in easily accessible locations. I first observed flying foxes there when I visited in 2013 and the island officially became my research site in 2014.

Ayesha: What does their habitat look like on this particular island? Is proximity to food and water a factor for them in choosing a roosting site?

Dr. Sheema: It depends on what you mean by ‘habitat’! The flying foxes themselves roost right in the middle of villages – they live amongst humans! But, they appear to be feeding in a variety of different habitats all over the island –rainforest, mangroves, and in people’s orchards and back gardens. We’re not really sure at this point what exact factors influence their choice of roosting site. However, on Tioman we suspect that they roost in human areas because they feel no threat from the locals. That is because the local communities on the island are mostly ethnic Malays, who practice Islam. You may already know this, but Muslims don’t eat bats due to religious dietary restrictions and therefore they don’t hunt them.

Ayesha: While reading about your work I got the sense that one of the preliminary questions you focused in your research was what do flying foxes eat on Tioman Island? What were your findings?

Dr. Sheema: Yes – I had to start by answering that very basic question first, because as I have previously stated the research had never been done before, so we had no idea! I found that the number one favourite food that comprises the core diet of Tioman’s flying foxes is wild figs from the forest. However, when people’s mango trees are fruiting, mango fruits make up an important part of their diet too. We, also, have video footage proving that flying foxes feed on nectar from durian flowers. Our dietary analysis is still very preliminary though so I’m quite confident that in time if we improve our techniques and approach we’ll be able to identify more food plants that they feed on.

Ayesha: How do you find out what they eat?

Dr. Sheema: The easiest way to find out is to collect flying fox poop and analyse what’s in it. Traditionally, researchers have done this by using microscopes to identify seeds and pollen grains. But, it’s really tough to do this if you don’t have a reference collection to compare with! So, we tried a new approach using molecular analysis. We were successful in identifying plant DNA in the flying fox poop, which tells us what plants the flying foxes were feeding on. Another method that we’re hoping to test out in the future is satellite tracking – fixing the bats with collars containing satellite transmitters that will tell us where the bats go to forage.

Ayesha: You mentioned that you have video footage of flying foxes feeding on nectar from durian flower. Was installing camera traps in the durian tree part of the effort to learn about their diet?

Dr. Sheema: The camera traps in durian trees were not really a method to determine what the flying foxes were eating – we already knew they were feeding on durian flowers because we had identified durian pollen grains in the feces. The camera traps were to help us determine the feeding behaviour of flying foxes in the durian trees and to identify any other animal visitors along with their feeding behaviour too.

Ayesha: Given that the research that you are conducting on the flying foxes is our first glimpse into the lives of these creatures for the Malaysian Peninsula every new finding or observation must be exciting. With that in mind, I am curious to learn about what kind of behavior the camera traps revealed. Had you hypothesized something and were you proven right, or did the footage contradict your hypothesis?

Dr. Sheema: Well I didn’t really have a specific hypothesis. I wanted to use the camera traps to investigate whether the flying foxes were actually pollinating the durian flower. I wanted to believe that this was true because we had already discovered durian pollen in their droppings, but I was a bit skeptical about them being pollinators due to their large size. I was concerned that they might damage the flower in the process of feeding. But I was really blown away when I saw the video. There was irrefutable evidence that the flying foxes were indeed pollinating the durian flower! Despite their size they were not damaging the flowers. In fact, in some cases they were actually feeding quite delicately! I was also pleasantly surprised to learn how hardy and robust durian flowers really are!

Pic 1 : Spot the flying fox in action in this camera trap image! Pic 2: Close up of the durian flower that the flying foxes love to feed on!

Click on the images to enlarge

Click on the images to enlarge

Ayesha: That is fascinating but let’s back up for a second and talk about the durian tree. By virtue of being a rainforest tree the durian trees I am guessing are very tall. So placing camera traps on these trees is probably quite a feat! Can you please walk us through this process of what it takes to place a camera trap in the tree canopy?

Dr. Sheema: Yes, one of the trees was around 90 years old, and 25 meters (82 feet) high! It’s not easy to get up there, and we had to be mindful of the health and safety risks especially since there were a lot of aggressive honeybees around. So, we collaborated with professional tree-climbers, who had the right kind of equipment and experience to put the camera traps in the trees. I provided instructions, direction, and guidance from the ground to ensure that they placed the cameras in the best possible locations and positions, aimed at clusters of flowers. Finally, they used cable ties to secure the cameras to the branches.

Dr. Sheema: Yes, one of the trees was around 90 years old, and 25 meters (82 feet) high! It’s not easy to get up there, and we had to be mindful of the health and safety risks especially since there were a lot of aggressive honeybees around. So, we collaborated with professional tree-climbers, who had the right kind of equipment and experience to put the camera traps in the trees. I provided instructions, direction, and guidance from the ground to ensure that they placed the cameras in the best possible locations and positions, aimed at clusters of flowers. Finally, they used cable ties to secure the cameras to the branches.

Pic 1 : Professional climber climbing the durian tree Pic 2: Try to spot the climber in the tree canopy.

Click on the images to enlarge

Click on the images to enlarge

Ayesha: Do you know if flying foxes travel long distances to find food or do they stay close to their roost site? Do they eat only wild fruits, or do they pretty much enjoy any available fruit?

Dr. Sheema: This differs somewhat according to species and country. In general, though many flying fox species can and do travel long distances to forage and feed. In fact, the study I mentioned earlier (Epstein et al in 2009 on P. vampyrus) used satellite tracking to study how far this particular species of flying foxes travel. Interestingly, they found that they can travel up to 87.5km in just one single night in search of food! In terms of food, flying foxes are known as generalists, meaning that they’re flexible with their diet, and they can adapt to different kinds of food sources. They feed on fruits, flowers, nectar, leaves, even twigs and bark – and their food plants can be either wild or cultivated species.

Ayesha: In the process of foraging for themselves do they provide any eco-services? What is their role in our ecosystem?

Dr. Sheema: Oh yes, flying foxes provide us with all kinds of beneficial ecosystem services! This is because they play a very important dual role as seed dispersers and also, pollinators. When they feed on fruit, they often carry them off and fly away from the parent tree, which means that the seeds later get dropped in other places. When they swallow really small seeds, the seeds later get defecated elsewhere, often in mid-flight. At the same time, when they feed on nectar from flowers, their fur gets covered in pollen. The bats then move off and transfer this pollen to other flowers as they continue feeding. So, as they fly around they’re really acting like gardeners, helping to plant and maintain the health of rainforests and other ecosystems in the tropics and sub-tropics.

Also, as stated earlier, my research uncovered evidence proving that flying foxes are actually helping pollinate Durio zibethinus, durian trees, thus helping to produce healthy durian fruit. Given how culturally* and economically* important the durian industry is in Southeast Asia, the significance of this role really cannot be ignored.

* Editor’s notes: In Southeast Asia, the durian fruit is known as the “King of Fruits” and is highly coveted for its unique flavor, texture, and taste. A recent article estimated a total of 568 million dollars in durian exports to China from Thailand and Malaysia which amounts to about 299 thousand tons in weight. While Malaysia is the second largest exporter of durian most of the fruit is consumed locally. In 2014 an estimated 349 thousand tons of durian was consumed locally in Malaysia.

Dr. Sheema: This differs somewhat according to species and country. In general, though many flying fox species can and do travel long distances to forage and feed. In fact, the study I mentioned earlier (Epstein et al in 2009 on P. vampyrus) used satellite tracking to study how far this particular species of flying foxes travel. Interestingly, they found that they can travel up to 87.5km in just one single night in search of food! In terms of food, flying foxes are known as generalists, meaning that they’re flexible with their diet, and they can adapt to different kinds of food sources. They feed on fruits, flowers, nectar, leaves, even twigs and bark – and their food plants can be either wild or cultivated species.

Ayesha: In the process of foraging for themselves do they provide any eco-services? What is their role in our ecosystem?

Dr. Sheema: Oh yes, flying foxes provide us with all kinds of beneficial ecosystem services! This is because they play a very important dual role as seed dispersers and also, pollinators. When they feed on fruit, they often carry them off and fly away from the parent tree, which means that the seeds later get dropped in other places. When they swallow really small seeds, the seeds later get defecated elsewhere, often in mid-flight. At the same time, when they feed on nectar from flowers, their fur gets covered in pollen. The bats then move off and transfer this pollen to other flowers as they continue feeding. So, as they fly around they’re really acting like gardeners, helping to plant and maintain the health of rainforests and other ecosystems in the tropics and sub-tropics.

Also, as stated earlier, my research uncovered evidence proving that flying foxes are actually helping pollinate Durio zibethinus, durian trees, thus helping to produce healthy durian fruit. Given how culturally* and economically* important the durian industry is in Southeast Asia, the significance of this role really cannot be ignored.

* Editor’s notes: In Southeast Asia, the durian fruit is known as the “King of Fruits” and is highly coveted for its unique flavor, texture, and taste. A recent article estimated a total of 568 million dollars in durian exports to China from Thailand and Malaysia which amounts to about 299 thousand tons in weight. While Malaysia is the second largest exporter of durian most of the fruit is consumed locally. In 2014 an estimated 349 thousand tons of durian was consumed locally in Malaysia.

Pic 1: Clusters of the durian flower. Pic 2: Durian fruit.in the tree. Notice how high the durian tree canopy is

compared to the other trees!

Click on the images to enlarge

compared to the other trees!

Click on the images to enlarge

Ayesha: You mentioned earlier that they sometimes help themselves to fruit from orchards and people’s backyards I can see how that might become an issue for the growers. How do the local communities respond to that? In other words, is human-animal conflict an issue and a threat to their survival?

Dr. Sheema: Human-bat conflict is definitely a problem that threatens the survival of flying foxes. In particular, there is a very real conflict between fruit growers and fruit bats. Flying foxes get a bad rap because growers say the bats fly into orchards and plantations at night, causing damage to fruits and flowers as they feed, which then leads to financial loss. Consequently, many fruit growers hate bats and routinely kill them in order to protect their fruit crops.

Ayesha: What are the other threats they face within Malaysia?

Dr. Sheema: As I stated earlier, the flying foxes on Tioman live among people because they are not hunted on that island. The bats on Tioman are lucky. However, other flying fox populations in Malaysia are not so lucky. Infact, the single greatest threat to flying foxes in Malaysia is hunting. Here, flying foxes are hunted for consumption as medicine and exotic food. Some local people of Chinese ethnicity believe that consuming flying fox meat can cure asthma, and is good for their health. While there is no scientific evidence to support this claim you will often find flying fox meat offered on the menu in certain local Chinese restaurants. Additionally, in Borneo, where flying foxes are consumed by indigenous people, you will find flying foxes meat for sale in the local markets. Deforestation for logging, agriculture, and infrastructure development, including clearance of mangroves for aquaculture and land reclamation, destroys their habitat and food sources. So, flying foxes are really getting hammered from all angles. As you can see, there are a myriad of interconnecting threats driving them to extinction in this country.

Ayesha: What is their IUCN status? Are flying foxes listed as vulnerable, threatened, or endangered?

Dr. Sheema: That depends on the specific species. You can check the IUCN status of individual flying fox species on the online Red List database. However, Malaysia has also come up with our own ‘Red List of Mammals for Peninsular Malaysia’. It lists the country’s two flying fox species (P. hypomelanus and P. vampyrus) as ‘Endangered’. This is in contrast to the global IUCN Red List which lists P. hypomelanus as ‘Least Concern’, and P. vampyrus as ‘Vulnerable’, based on global data showing these two species to be common and widespread. Such an approach overlooks localised threats and contexts and therefore makes it extremely hard to secure conservation attention and funding for flying fox conservation in Malaysia. This underscores the importance of taking localised conservation action to address country-specific flying fox declines, which have wider ecosystem implications on a national and also transboundary level. It’s really crucial to recognise and address these kinds of localised conservation issues.

Ayesha: Why is it so important to save local flying fox populations?

Dr. Sheema: As I previously stated, it’s crucial to maintain healthy flying fox populations in order to sustain healthy ecosystems! They play an important role as seed dispersers and pollinators; if they disappear there could be disastrous knock-on effects in rainforests and mangroves – potentially even affecting coral reefs and marine ecosystems,

Often efforts are focused on species that are officially classified as globally endangered, rare, or endemic. This is a real problem, because a species may become locally extinct simply because it’s considered to be globally common and therefore is not a conservation priority. This could have very serious implications for the local economy, ecosystems, and other associated species, which flying foxes help to maintain. But we might not find out until it’s too late, and the damage is already done. Restoration and recovery then becomes so much harder – maybe even impossible. Also, Malaysia’s two flying fox species may be considered globally common and widespread – but they’re the only flying fox species that we have here! If they go extinct locally then we would have lost all our flying foxes. That would be a real tragedy for the country.

Ayesha: Does Malaysia have wildlife protection policies that give legal protective status to threaten or endangered species like the flying foxes? If yes, can you elaborate on those policies?

Dr. Sheema: The legal and jurisdictional situations differ between Peninsular Malaysia and Malaysian Borneo. Under Peninsular Malaysia’s Wildlife Conservation Act 2010, flying foxes are listed on the ‘Protected’ list. This means that they can be hunted legally with a license. The same situation applies with Sabah’s Wildlife Conservation Enactment 1997. However, the Department of Wildlife and National Parks Peninsular Malaysia has finally recognized the severe extinction risk that hunting poses to flying foxes, and is now taking steps to move them to the ‘Totally Protected’ list, which means that hunting of flying foxes will be completely outlawed in all states on the Peninsula. This is a long overdue Peninsula-wide ban on hunting! I’m hoping these legal changes will finally come into effect this year. Meanwhile, in Sarawak, all bats are already protected under their Wild Life Protection Ordinance 1998.

Ayesha: Are wildlife protection policies enough to safeguard the species? What do you envision the next steps to be for conservation to be effective?

Dr. Sheema: There are actually several types of conservation actions that need to be implemented concurrently in order to save flying foxes in Peninsular Malaysia. Policies officially protecting flying fox species from hunting are definitely a necessary first step. However, on their own they’re not enough – there is a lot of illegal hunting going on. So, the wildlife protection laws need to be enforced effectively. We also need: 1) Legal protection and conservation of roost sites; 2) Outreach with local communities to raise awareness and promote appreciation of flying foxes; and 3) Efforts to understand and mitigate the conflict between fruit farmers and fruit bats.

Ayesha: Given that bats are viewed negatively because of rabies, crop damage and superstitious beliefs what were some of the challenges you faced (and continue to face) when you advocate for their conservation? What do you do to present the species in a better light so people care for them?

Dr. Sheema: In Asia there aren’t that many superstitious beliefs around bats actually. In traditional Chinese culture, they’re actually viewed as auspicious symbols. Also, bat-borne rabies is not currently an issue in Asia – there have been no known records of bats transmitting rabies to humans here. However, bats are still definitely uncharismatic, unpopular animals that are frequently viewed as pests inconveniencing humans. There is low awareness of why bats are important, and why we need to conserve them. This makes it difficult to convince people to like bats, and to support their conservation. Highlighting the important ecosystem services provided by bats – especially durian pollination is an important approach that will probably be our best bet for getting people in Southeast Asia to care about these animals.

* Editor’s notes (repeated): In Southeast Asia, the durian fruit is known as the “King of Fruits” and is highly coveted for its unique flavor, texture, and taste. A recent article estimated a total of 568 million dollars in durian exports to China from Thailand and Malaysia which amounts to about 299 thousand tons in weight. While Malaysia is the second largest exporter of durian most of the fruit is consumed locally. In 2014 and estimated 349 thousand tons of durian was consumed locally in Malaysia.

Ayesha: What is the most awe-inspiring thing about the flying foxes that you want the readers to remember?

Dr. Sheema: They’re such amazing creatures that play such an important role in rainforests and other tropical ecosystems. They help to maintain the delicate balance in nature, which then also helps to ensure the wellbeing of us humans. We need them around!

Ayesha: Yes, indeed we certainly do need them around and after interviewing you I have a whole new level of appreciation for them! Thank you for educating us about the flying foxes. It sure has been fun learning about your work especially being able to get a sneak peek into the preliminary findings and what is yet to come. I wish you the very best as you expand your scope to include other flying fox species! I’ll visit your website periodically for updates and I encourage the readers to do the same!

Dr. Sheema: You are welcome!

Dr. Sheema: Human-bat conflict is definitely a problem that threatens the survival of flying foxes. In particular, there is a very real conflict between fruit growers and fruit bats. Flying foxes get a bad rap because growers say the bats fly into orchards and plantations at night, causing damage to fruits and flowers as they feed, which then leads to financial loss. Consequently, many fruit growers hate bats and routinely kill them in order to protect their fruit crops.

Ayesha: What are the other threats they face within Malaysia?

Dr. Sheema: As I stated earlier, the flying foxes on Tioman live among people because they are not hunted on that island. The bats on Tioman are lucky. However, other flying fox populations in Malaysia are not so lucky. Infact, the single greatest threat to flying foxes in Malaysia is hunting. Here, flying foxes are hunted for consumption as medicine and exotic food. Some local people of Chinese ethnicity believe that consuming flying fox meat can cure asthma, and is good for their health. While there is no scientific evidence to support this claim you will often find flying fox meat offered on the menu in certain local Chinese restaurants. Additionally, in Borneo, where flying foxes are consumed by indigenous people, you will find flying foxes meat for sale in the local markets. Deforestation for logging, agriculture, and infrastructure development, including clearance of mangroves for aquaculture and land reclamation, destroys their habitat and food sources. So, flying foxes are really getting hammered from all angles. As you can see, there are a myriad of interconnecting threats driving them to extinction in this country.

Ayesha: What is their IUCN status? Are flying foxes listed as vulnerable, threatened, or endangered?

Dr. Sheema: That depends on the specific species. You can check the IUCN status of individual flying fox species on the online Red List database. However, Malaysia has also come up with our own ‘Red List of Mammals for Peninsular Malaysia’. It lists the country’s two flying fox species (P. hypomelanus and P. vampyrus) as ‘Endangered’. This is in contrast to the global IUCN Red List which lists P. hypomelanus as ‘Least Concern’, and P. vampyrus as ‘Vulnerable’, based on global data showing these two species to be common and widespread. Such an approach overlooks localised threats and contexts and therefore makes it extremely hard to secure conservation attention and funding for flying fox conservation in Malaysia. This underscores the importance of taking localised conservation action to address country-specific flying fox declines, which have wider ecosystem implications on a national and also transboundary level. It’s really crucial to recognise and address these kinds of localised conservation issues.

Ayesha: Why is it so important to save local flying fox populations?

Dr. Sheema: As I previously stated, it’s crucial to maintain healthy flying fox populations in order to sustain healthy ecosystems! They play an important role as seed dispersers and pollinators; if they disappear there could be disastrous knock-on effects in rainforests and mangroves – potentially even affecting coral reefs and marine ecosystems,

Often efforts are focused on species that are officially classified as globally endangered, rare, or endemic. This is a real problem, because a species may become locally extinct simply because it’s considered to be globally common and therefore is not a conservation priority. This could have very serious implications for the local economy, ecosystems, and other associated species, which flying foxes help to maintain. But we might not find out until it’s too late, and the damage is already done. Restoration and recovery then becomes so much harder – maybe even impossible. Also, Malaysia’s two flying fox species may be considered globally common and widespread – but they’re the only flying fox species that we have here! If they go extinct locally then we would have lost all our flying foxes. That would be a real tragedy for the country.

Ayesha: Does Malaysia have wildlife protection policies that give legal protective status to threaten or endangered species like the flying foxes? If yes, can you elaborate on those policies?

Dr. Sheema: The legal and jurisdictional situations differ between Peninsular Malaysia and Malaysian Borneo. Under Peninsular Malaysia’s Wildlife Conservation Act 2010, flying foxes are listed on the ‘Protected’ list. This means that they can be hunted legally with a license. The same situation applies with Sabah’s Wildlife Conservation Enactment 1997. However, the Department of Wildlife and National Parks Peninsular Malaysia has finally recognized the severe extinction risk that hunting poses to flying foxes, and is now taking steps to move them to the ‘Totally Protected’ list, which means that hunting of flying foxes will be completely outlawed in all states on the Peninsula. This is a long overdue Peninsula-wide ban on hunting! I’m hoping these legal changes will finally come into effect this year. Meanwhile, in Sarawak, all bats are already protected under their Wild Life Protection Ordinance 1998.

Ayesha: Are wildlife protection policies enough to safeguard the species? What do you envision the next steps to be for conservation to be effective?

Dr. Sheema: There are actually several types of conservation actions that need to be implemented concurrently in order to save flying foxes in Peninsular Malaysia. Policies officially protecting flying fox species from hunting are definitely a necessary first step. However, on their own they’re not enough – there is a lot of illegal hunting going on. So, the wildlife protection laws need to be enforced effectively. We also need: 1) Legal protection and conservation of roost sites; 2) Outreach with local communities to raise awareness and promote appreciation of flying foxes; and 3) Efforts to understand and mitigate the conflict between fruit farmers and fruit bats.

Ayesha: Given that bats are viewed negatively because of rabies, crop damage and superstitious beliefs what were some of the challenges you faced (and continue to face) when you advocate for their conservation? What do you do to present the species in a better light so people care for them?

Dr. Sheema: In Asia there aren’t that many superstitious beliefs around bats actually. In traditional Chinese culture, they’re actually viewed as auspicious symbols. Also, bat-borne rabies is not currently an issue in Asia – there have been no known records of bats transmitting rabies to humans here. However, bats are still definitely uncharismatic, unpopular animals that are frequently viewed as pests inconveniencing humans. There is low awareness of why bats are important, and why we need to conserve them. This makes it difficult to convince people to like bats, and to support their conservation. Highlighting the important ecosystem services provided by bats – especially durian pollination is an important approach that will probably be our best bet for getting people in Southeast Asia to care about these animals.

* Editor’s notes (repeated): In Southeast Asia, the durian fruit is known as the “King of Fruits” and is highly coveted for its unique flavor, texture, and taste. A recent article estimated a total of 568 million dollars in durian exports to China from Thailand and Malaysia which amounts to about 299 thousand tons in weight. While Malaysia is the second largest exporter of durian most of the fruit is consumed locally. In 2014 and estimated 349 thousand tons of durian was consumed locally in Malaysia.

Ayesha: What is the most awe-inspiring thing about the flying foxes that you want the readers to remember?

Dr. Sheema: They’re such amazing creatures that play such an important role in rainforests and other tropical ecosystems. They help to maintain the delicate balance in nature, which then also helps to ensure the wellbeing of us humans. We need them around!

Ayesha: Yes, indeed we certainly do need them around and after interviewing you I have a whole new level of appreciation for them! Thank you for educating us about the flying foxes. It sure has been fun learning about your work especially being able to get a sneak peek into the preliminary findings and what is yet to come. I wish you the very best as you expand your scope to include other flying fox species! I’ll visit your website periodically for updates and I encourage the readers to do the same!

Dr. Sheema: You are welcome!

Who to support:

Please find listed below organizations dedicated to preserving bat populations around the world. Please take a few minutes to visit their website to pledge your support by signing petitions, volunteering your time, making a donation, and staying informed. Should you wish to make a contribution please send your contributions directly to an organization of your choice.

Rimba

Lubee Bat Conservancy

Southeast Asian Bat Conservation Research Unit (SEABCRU)

Philippines Biodiversity Conservation Organisation

Mauritian Wildlife Foundation

North American Bat Conservation Alliance

Bat Conservation International: Bat Conservation International has a global presence. Please click here to look for a region closest to you. .

UNEP/Eurobats : Listed on this website are non-profits working to conserve bats. Click on the country name to find a local organization near you.

Please find listed below organizations dedicated to preserving bat populations around the world. Please take a few minutes to visit their website to pledge your support by signing petitions, volunteering your time, making a donation, and staying informed. Should you wish to make a contribution please send your contributions directly to an organization of your choice.

Rimba

Lubee Bat Conservancy

Southeast Asian Bat Conservation Research Unit (SEABCRU)

Philippines Biodiversity Conservation Organisation

Mauritian Wildlife Foundation

North American Bat Conservation Alliance

Bat Conservation International: Bat Conservation International has a global presence. Please click here to look for a region closest to you. .

UNEP/Eurobats : Listed on this website are non-profits working to conserve bats. Click on the country name to find a local organization near you.

Web Design and Site Managed by Sarah Siraj

Content Research and Photographs by Ayesha Siraj

Content Research and Photographs by Ayesha Siraj

- Home

- My Story

- Current Issue

-

Past Issues

- Anniversary Edition (5 year)

- Bald Eagle >

- Climate Change

- Common Sense Advocacy

- Conversations on Conservation I

- Conversations on Conservation II

- Conversations on Conservation - Part III

- Conversations on Conservation: Part IV

- Conversations on Conservations: Part V

- Conversations on Conservation: Part VI

- Coral Reef >

- Ecology, Economics and Evolution

- Elephant

- Flying Fox

- Gopher Tortoise, Eastern Indigo Snake and Gopher Frog >

- Honeybee >

- Invasive Species

- Lion

- Monarch Butterfly

- Native Orchids >

- Pitcher Plant Moth, Happy-Face Spider & Ogre-Faced Spider

- Tiger >

- Water

- How can you help?

- More...