In Spotlight: Anniversary Edition

Kihansi Spray Toad, Tennessee Purple Coneflower, Tiger and Humpback Whale

|

With the release of this edition, Wildlife In Spotlight celebrates its 5th anniversary. It has been a privilege to stand for wildlife and an honor to bring their stories to light. I am grateful to all of you for your readership and am encouraged that the website has welcomed over 10,000 visitors to date. I hope the content has provided a deeper understanding of interconnectedness in the web of life and has motivated everyone to take a small yet meaningful step towards preserving our biodiversity.

While the health of our planet continues to be a concern, I am optimistic that when citizens like you engage, we can pivot the trajectory of our planet from destruction to recovery. To demonstrate that, in this special anniversary edition, we focus on species which have shown promise in recovery in the last few years. This newsletter in divided into five segments. The first four segments showcase the Spotlight species; the Kihansi spray toad, Tennessee purple coneflower, the tiger, and the humpback whale. The fifth segment includes some of the species that have recovered in the recent past. |

The Kihansi Spray Toad

Tinted in the golden hue of the late afternoon sun, the vast expanse of the Serengeti anticipates nightfall. The long shadows give way to silhouettes of wildlife and trees against the radiant orange sky. Slowly the sun slips under the horizon and the amber tones concede to the starlit night. The cool evening breeze rustles through the tall grass and the silence is broken by a symphony of croaking frogs. Nightlife is just beginning with the distance calls of hyenas.

The Serengeti, the world-renowned national park in Tanzania, boasts the Big Five (lions, leopards, elephants, African buffalo, and rhinoceroses) and hosts the largest mammal migration on land. Sharing the beautiful landscape of Tanzania is a lesser-known species, the Kihansi spray toad, which lives approximately 900 kms (approx 560 miles) south of the Serengeti National Park.

Habitat: The toad was discovered in 1996 and is only known to live in a four hectare wetland habitat created by a 3,000 feet waterfall fed by the Kihansi River. The immense waterfall creates constant mist in the gorge which the toad is highly reliant on for its survival.

Threats: The construction of a hydroelectric dam in 2000 on the Kihansi River permanently altered the habitat of the toad by restricting about 90% of the water from flowing into the gorge. With the waterfall volume down, the mist disappeared which in turn led to the extinction of the species in the wild. Although the hydroelectric dam was beneficial to the people of Tanzania, it unfortunately contributed to the species losing its unique habitat.

Along with the loss of the mist zone, the toad suffered another blow. A deadly fungus called chytrid, which has caused population declines in amphibian species across the globe, also infected the toad. Scientists have been working on finding a cure but there has been no breakthrough in discovering a treatment yet.

Protective Status: The Kihansi spray toad was declared extinct in the wild in 2009

Recovery: As the implications of habitat loss became evident, the Tanzanian government invited scientists to collect close to 500 Kihansi spray toads from the wild. These individuals were transferred to two locations in the United States, the Bronx Zoo in New York and the Toledo Zoo in Ohio, for safekeeping. Given that this was the first time a captive breeding program was being established for the spray toad, the researchers were faced with many challenges. To ensure the success of the program, they had to closely monitor their diet, health, density ratio within each enclosure, and provide a constant misting zone critical to their survival. Additionally, they also needed to establish the right balance of disease and pathogens within the laboratory setting to simulate their natural environment.

In the meantime, with aid provided by the World Bank, the Tanzanian government built an extensive misting system in the Kihansi gorge to replicate the toad’s natural habitat. After almost a decade of captive breeding, about 100 toads were sent back to the University of Dar es Salaam in Tanzania and they started their own safeguarding breeding program. An experimental release and testing was undertaken shortly thereafter. The results suggested that the captive bred toads were adapting well in the wild. Backed by these findings, during the years 2012 to 2016, approximately 8,000 Kihansi spray toads were reintroduced into the Kihansi Gorge. The releases have been successful and their prognosis has been promising.

The successful recovery of the Kihansi spray toad from the brink of extinction is a testament to the possibility of what can be overcome and proof that we can coexist with wildlife.

The Serengeti, the world-renowned national park in Tanzania, boasts the Big Five (lions, leopards, elephants, African buffalo, and rhinoceroses) and hosts the largest mammal migration on land. Sharing the beautiful landscape of Tanzania is a lesser-known species, the Kihansi spray toad, which lives approximately 900 kms (approx 560 miles) south of the Serengeti National Park.

Habitat: The toad was discovered in 1996 and is only known to live in a four hectare wetland habitat created by a 3,000 feet waterfall fed by the Kihansi River. The immense waterfall creates constant mist in the gorge which the toad is highly reliant on for its survival.

Threats: The construction of a hydroelectric dam in 2000 on the Kihansi River permanently altered the habitat of the toad by restricting about 90% of the water from flowing into the gorge. With the waterfall volume down, the mist disappeared which in turn led to the extinction of the species in the wild. Although the hydroelectric dam was beneficial to the people of Tanzania, it unfortunately contributed to the species losing its unique habitat.

Along with the loss of the mist zone, the toad suffered another blow. A deadly fungus called chytrid, which has caused population declines in amphibian species across the globe, also infected the toad. Scientists have been working on finding a cure but there has been no breakthrough in discovering a treatment yet.

Protective Status: The Kihansi spray toad was declared extinct in the wild in 2009

Recovery: As the implications of habitat loss became evident, the Tanzanian government invited scientists to collect close to 500 Kihansi spray toads from the wild. These individuals were transferred to two locations in the United States, the Bronx Zoo in New York and the Toledo Zoo in Ohio, for safekeeping. Given that this was the first time a captive breeding program was being established for the spray toad, the researchers were faced with many challenges. To ensure the success of the program, they had to closely monitor their diet, health, density ratio within each enclosure, and provide a constant misting zone critical to their survival. Additionally, they also needed to establish the right balance of disease and pathogens within the laboratory setting to simulate their natural environment.

In the meantime, with aid provided by the World Bank, the Tanzanian government built an extensive misting system in the Kihansi gorge to replicate the toad’s natural habitat. After almost a decade of captive breeding, about 100 toads were sent back to the University of Dar es Salaam in Tanzania and they started their own safeguarding breeding program. An experimental release and testing was undertaken shortly thereafter. The results suggested that the captive bred toads were adapting well in the wild. Backed by these findings, during the years 2012 to 2016, approximately 8,000 Kihansi spray toads were reintroduced into the Kihansi Gorge. The releases have been successful and their prognosis has been promising.

The successful recovery of the Kihansi spray toad from the brink of extinction is a testament to the possibility of what can be overcome and proof that we can coexist with wildlife.

Did you know?

The Kihansi spray toad is among only a few species of toads which do not have an egg or tadpole stage. Their young are fully formed toads at birth.

The Kihansi spray toad is among only a few species of toads which do not have an egg or tadpole stage. Their young are fully formed toads at birth.

Photo credit: Toledo Zoo (All images used with permission)

Read more about the efforts of Toledo Zoo to preserve the Kihansi spray toad.

Read more about the efforts of Toledo Zoo to preserve the Kihansi spray toad.

Tennessee Purple Coneflower

It may come as a surprise to many of us, but a number of species of plants and trees are also listed as Threatened or Endangered under the Endangered Species Act. One such plant to be listed as a high priority conservation species was the Tennessee purple coneflower. This North American native has purple pink daisy-like flowers and thrives in the dry summer heat. Its long blooming cycle makes it a favorite among bees and butterflies and its spent flowers provide seeds for the American goldfinch.

Habitat: The Tennessee purple coneflower is endemic (found nowhere else in the world) to a 66 square mile area in Middle Tennessee. It grows in a unique ecosystem known as the limestone cedar glade. Its distinct topography consists of limestone bedrock with a very shallow layer of dirt, which makes it hard for most trees and plants to grow or establish. Fortunately for the Tennessee purple coneflower its long taproot can grow through crevices in the limestone to reach moisture. The presence of this beautiful flower in such an inhospitable and rugged terrain speaks to how well it is adapted to its environment.

Threats: Loss of habitat due to urbanization, development, off-road driving, and illegal dumping (trash, motor oil, old appliances).

Protective Status: Listed as Endangered in 1979. Delisted to Threatened in September 2011.

Recovery: The Tennessee purple coneflower was discovered in the 1800s but was considered extinct for several decades. It was rediscovered in 1969 by a botanist Dr. Elise Quarterman. She is not only credited for finding the lost plant but she was also instrumental in laying the groundwork to protect its habitat and getting it listed as Endangered. The next steps to conserving the species were guided by Dr. Thomas Hammerly, a student of Dr. Quarterman. His research decoded the lifecycle of the plant and highlighted its twin-tracked adaptation to survival. The plant propagates by producing seeds as well as clones. Seed dispersal allowed new plants and colonies to establish and cloning ensured longevity to the existing plant. Once the science of the plant was understood, several public and private partners worked together over the course of 30 years to collect and propagate seeds, and to carefully select sites for outplanting in the limestone cedar glades. That was followed by countless hours of closely monitoring and analyzing the plants and its ecology.

Finally, after three decades of considerable research and protection, the Tennessee purple coneflower was delisted from Endangered to Threatened in 2011. According to the US Fish and Wildlife Service, “The Tennessee purple coneflower now exists in 35 colonies; 15 of these are wild colonies, and 20 were established through introductions of seed or nursery propagated plants. Nineteen of the 35 colonies are considered secure from threats and are self sustaining.”

I recently caught up with Dr. Kim Sadler, Co-Director of the Center for Cedar Glades Studies and asked her what the coneflower symbolized and she said, “The delisting of the Tennessee purple coneflower from endangered to threatened status is a story of hope. It is an example of what is possible when science and policy align, when conservation agencies work together, and when support is provided. It stands as an example of a conservation effort that demonstrates that change is possible.”

Habitat: The Tennessee purple coneflower is endemic (found nowhere else in the world) to a 66 square mile area in Middle Tennessee. It grows in a unique ecosystem known as the limestone cedar glade. Its distinct topography consists of limestone bedrock with a very shallow layer of dirt, which makes it hard for most trees and plants to grow or establish. Fortunately for the Tennessee purple coneflower its long taproot can grow through crevices in the limestone to reach moisture. The presence of this beautiful flower in such an inhospitable and rugged terrain speaks to how well it is adapted to its environment.

Threats: Loss of habitat due to urbanization, development, off-road driving, and illegal dumping (trash, motor oil, old appliances).

Protective Status: Listed as Endangered in 1979. Delisted to Threatened in September 2011.

Recovery: The Tennessee purple coneflower was discovered in the 1800s but was considered extinct for several decades. It was rediscovered in 1969 by a botanist Dr. Elise Quarterman. She is not only credited for finding the lost plant but she was also instrumental in laying the groundwork to protect its habitat and getting it listed as Endangered. The next steps to conserving the species were guided by Dr. Thomas Hammerly, a student of Dr. Quarterman. His research decoded the lifecycle of the plant and highlighted its twin-tracked adaptation to survival. The plant propagates by producing seeds as well as clones. Seed dispersal allowed new plants and colonies to establish and cloning ensured longevity to the existing plant. Once the science of the plant was understood, several public and private partners worked together over the course of 30 years to collect and propagate seeds, and to carefully select sites for outplanting in the limestone cedar glades. That was followed by countless hours of closely monitoring and analyzing the plants and its ecology.

Finally, after three decades of considerable research and protection, the Tennessee purple coneflower was delisted from Endangered to Threatened in 2011. According to the US Fish and Wildlife Service, “The Tennessee purple coneflower now exists in 35 colonies; 15 of these are wild colonies, and 20 were established through introductions of seed or nursery propagated plants. Nineteen of the 35 colonies are considered secure from threats and are self sustaining.”

I recently caught up with Dr. Kim Sadler, Co-Director of the Center for Cedar Glades Studies and asked her what the coneflower symbolized and she said, “The delisting of the Tennessee purple coneflower from endangered to threatened status is a story of hope. It is an example of what is possible when science and policy align, when conservation agencies work together, and when support is provided. It stands as an example of a conservation effort that demonstrates that change is possible.”

Did you know?

The Tennessee purple coneflower always faces east.

The Tennessee purple coneflower always faces east.

Photo Credit: Darel Hess (All images used with permission)

Tiger

The Asian continent is home to some of the world’s most spectacular biodiversity. For centuries the flora and fauna has evolved alongside civilization and has played a pivotal role in shaping religious, tribal, and social norms in the region. They have defined the ecological landscape and their existence is intrinsically woven into the very fabric of these cultures. Yet, human greed and constant competition for resources between man and animal threatens their survival, and none is more threatened than the tiger.

Habitat: Things have drastically changed in the last 100 years for tigers, the most iconic species of the Asian continent. Their habitat once spanned 21 countries, but they are now only found in 11. Tigers have lost 96% of their historic range. Four subspecies have gone extinct in the wild and fewer than 3,900 individuals of the remaining five subspecies exist in the wild, of which less than a third are breeding females.

Threats:

Protective Status:

Recovery: For decades, governments of some Tiger Range Countries (TRC) along with several NGOs and international partners have worked diligently to protect tigers and curtail illegal wildlife trade in tiger parts. While their efforts were commendable, the results were not nearly what they needed them to be to secure a future for wild tigers.

In an attempt to combat these ongoing challenges, governments of thirteen Tiger Range Countries* and partners of the Global Tiger Initiative* (GTI) met at the International Tiger Forum (ITF), in Saint Petersburg, Russia in 2010. The goal of the Forum was to collaborate and pool resources with the primary focus of doubling wild tiger numbers in Tiger Range Countries by 2022. The positive outcome of the Forum was that all participating governments endorsed the Global Tiger Recovery Program which included action items such as protecting tigers and their habitat, increased support to rangers, reducing the threat of poaching, and engaging local communities, to name a few. As a follow up to the 2010 Forum, all stakeholders met again in 2012 at the Second Asian Ministerial Conference on Tiger Conservation in Thimphu, Bhutan. The objective of this meeting was to assess progress, build on the existing agenda, and reaffirm each country’s commitment to protect tigers. Subsequently, the Thimphu Affirmative Nine-Point Action Agenda on Tiger Conservation was formalized (refer to Page 12).

Tracing the recovery of tigers nearly a decade after the meeting in 2010 in Russia, the news is both celebratory and somber. Governments of India, Nepal, Thailand, and Bhutan have all announced that wild tiger numbers have increased in their respective countries. Dr. John Goodrich, the Chief Scientist and the Director of the Tiger Program at Panthera agrees that progress has been made in India and Nepal; however, he errs on the conservative side in regards to progress in both Thailand and Bhutan. Dr.Goodrich explained that, while tiger numbers have increased in Thailand's Western Forest Complex, it does not have a recent science-based country-wide estimates to substantiate a country-wide increase and Bhutan’s first national survey showed good results but he awaits subsequent surveys to document those upward trends.

This edition is about success stories; however, I would be remiss if I did not report that wild tigers in Laos, Vietnam, and Cambodia have all gone extinct in recent years. This demonstrates that success in one or two countries does not translate to success across the region or for all subspecies of the tiger. There is much to be done and we have a long road ahead. Please continue to support organizations dedicated to safeguarding tigers. Be an advocate, demand action from elected officials, and most importantly, please make a monetary contribution to a tiger fund of your choice.

*13 Tiger Range Countries (TRC): Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Lao, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, Russian, Thailand, and Vietnam.

*Partners of the Global Tiger Initiative: World Bank, the Global Environment Facility, the Smithsonian Institution, Save the Tiger Fund, and over 40 non-governmental organizations that make up the International Tiger Coalition.

Did you know?

The tiger is known as an umbrella species.

What is an umbrella species and what is an “umbrella effect”?

Tigers are considered an umbrella species because of their large area requirements and the prey species on which they depend. Protect tigers and you are likely protecting their prey and much of the biodiversity in the entire ecosystem. This phenomena is known as the “umbrella effect.”

Read more: Tiger Edition (Fall 2015)

View: Photo Gallery (Tiger Edition, Fall 2015)

Habitat: Things have drastically changed in the last 100 years for tigers, the most iconic species of the Asian continent. Their habitat once spanned 21 countries, but they are now only found in 11. Tigers have lost 96% of their historic range. Four subspecies have gone extinct in the wild and fewer than 3,900 individuals of the remaining five subspecies exist in the wild, of which less than a third are breeding females.

Threats:

- Poaching: Poaching remains the single largest threat to the wild tiger populations. Tiger parts are used in Traditional Chinese Medicine in Asia.

- Loss of habitat: Deforestation and fragmentation of the tiger habitat due to logging or for planting monoculture crops like palm oil on a commercial scale has put the species in peril.

- Loss of prey: Human population growth and commercial development of land has pushed humans to live in close proximity to tiger habitat. These communities often rely on wildlife meat for sustenance, which directly competes with the tiger’s prey.

- Human-animal conflict: An ever-shrinking and prey-depleted habitat force tigers to go after livestock. Loss of livestock often leads to retaliatory killing of the tiger.

- Roads and other linear infrastructure: Roads fragment tiger habitat and put adult tigers and cubs at risk of road accidents, while old logging roads (which are no longer in use for logging but have remained open to the public) provide easy access for poachers to tiger habitat which was previously inaccessible.

Protective Status:

- The Bengal tiger, Amur tiger, and the Indochinese tiger are listed as Endangered.

- The Malayan tiger and the Sumatran tiger are listed as Critically Endangered.

- The Bali, Caspian, Javan, and South China tiger are all believed to be extinct in the wild.

Recovery: For decades, governments of some Tiger Range Countries (TRC) along with several NGOs and international partners have worked diligently to protect tigers and curtail illegal wildlife trade in tiger parts. While their efforts were commendable, the results were not nearly what they needed them to be to secure a future for wild tigers.

In an attempt to combat these ongoing challenges, governments of thirteen Tiger Range Countries* and partners of the Global Tiger Initiative* (GTI) met at the International Tiger Forum (ITF), in Saint Petersburg, Russia in 2010. The goal of the Forum was to collaborate and pool resources with the primary focus of doubling wild tiger numbers in Tiger Range Countries by 2022. The positive outcome of the Forum was that all participating governments endorsed the Global Tiger Recovery Program which included action items such as protecting tigers and their habitat, increased support to rangers, reducing the threat of poaching, and engaging local communities, to name a few. As a follow up to the 2010 Forum, all stakeholders met again in 2012 at the Second Asian Ministerial Conference on Tiger Conservation in Thimphu, Bhutan. The objective of this meeting was to assess progress, build on the existing agenda, and reaffirm each country’s commitment to protect tigers. Subsequently, the Thimphu Affirmative Nine-Point Action Agenda on Tiger Conservation was formalized (refer to Page 12).

Tracing the recovery of tigers nearly a decade after the meeting in 2010 in Russia, the news is both celebratory and somber. Governments of India, Nepal, Thailand, and Bhutan have all announced that wild tiger numbers have increased in their respective countries. Dr. John Goodrich, the Chief Scientist and the Director of the Tiger Program at Panthera agrees that progress has been made in India and Nepal; however, he errs on the conservative side in regards to progress in both Thailand and Bhutan. Dr.Goodrich explained that, while tiger numbers have increased in Thailand's Western Forest Complex, it does not have a recent science-based country-wide estimates to substantiate a country-wide increase and Bhutan’s first national survey showed good results but he awaits subsequent surveys to document those upward trends.

This edition is about success stories; however, I would be remiss if I did not report that wild tigers in Laos, Vietnam, and Cambodia have all gone extinct in recent years. This demonstrates that success in one or two countries does not translate to success across the region or for all subspecies of the tiger. There is much to be done and we have a long road ahead. Please continue to support organizations dedicated to safeguarding tigers. Be an advocate, demand action from elected officials, and most importantly, please make a monetary contribution to a tiger fund of your choice.

*13 Tiger Range Countries (TRC): Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Lao, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, Russian, Thailand, and Vietnam.

*Partners of the Global Tiger Initiative: World Bank, the Global Environment Facility, the Smithsonian Institution, Save the Tiger Fund, and over 40 non-governmental organizations that make up the International Tiger Coalition.

Did you know?

The tiger is known as an umbrella species.

What is an umbrella species and what is an “umbrella effect”?

Tigers are considered an umbrella species because of their large area requirements and the prey species on which they depend. Protect tigers and you are likely protecting their prey and much of the biodiversity in the entire ecosystem. This phenomena is known as the “umbrella effect.”

Read more: Tiger Edition (Fall 2015)

View: Photo Gallery (Tiger Edition, Fall 2015)

Photo credit: John Goodrich/www.panthera.org, (Image used with permission)

Humpback whale

The ocean is home to countless fish, exotic creatures, and other marine life that have yet to be discovered. That said, there are thousands of species of sea life known to us which swim, skim, jump through waves and undercurrents, and prompt us to study them. One of the species that has been studied extensively is the humpback whale.

Habitat: Humpback whales are found in most oceans throughout the world and they have been divided into 14 distinct populations. These toothless gentle giants are among the largest creatures of the ocean even though their diet consists of some of the tiniest marine life, such as krill and small schooling fish. They migrate seasonally to warmer waters to breed and calve and return to cooler waters during the summer months, where their prey is plentiful. The vast distances they travel between their breeding and feeding grounds makes these among the longest migrations undertaken by any sea mammals. Some humpbacks have been known to travel up to 5,000 miles every year.

.

Threats: Commercial whaling started in the 1700s. Humpback whales were primarily hunted for blubber and whale oil, both of which were used as lubricants and fuel for lighting lamps. Whale oil was refined and used to make other products such as soaps and candles. Given how predictable the migratory patterns of humpback whales are, hunting boats showed up in the same locations year after year. The indiscriminate killing of whales for almost two centuries reduced their population from their historic stocks which numbered in the tens of thousands to just a few hundred by 1985 and put the species at risk of extinction.

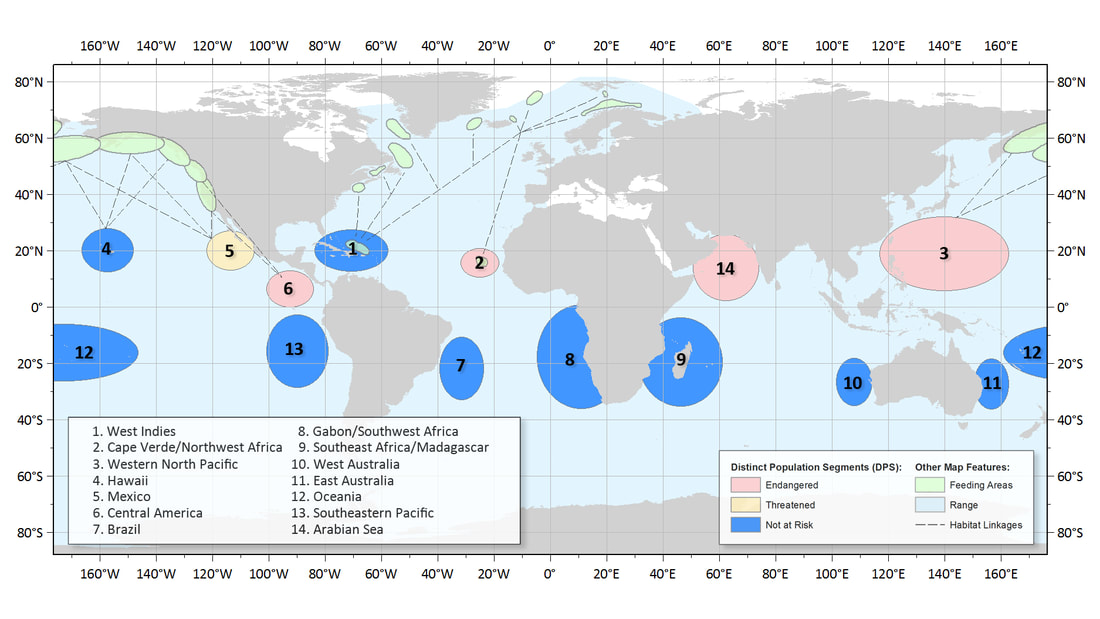

Protective Status: All humpback whales were listed as endangered in 1970. Of the 14 distinct populations, four are still listed as endangered and one is listed as threatened.(See map below)

Recovery: When the devastating impact of commercial whaling became apparent, countries around the world started imposing bans on commercial whaling. Eventually, a global moratorium on whale hunting was put into effect in 1986 by the International Whaling Commission (IWC). The ban provided the much-needed respite for the humpback whales and their numbers have since bounced back. While it is hard to count the exact number of whales within each of these 14 distinct populations, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) 2016 stock assessment reports provided a close approximate. NOAA estimated that 12 of those populations had more than 2,000 humpback whales each and two populations had fewer than 2,000. The humpback whale populations that live off the east and west coast of Australia boast numbers in the upward of 20,000 while the smallest known population which lives in the Arabian Sea is believed to have as few as 80 individuals.

In 2016, as a result of the successful recovery of the humpback whales, NOAA announced that 9 populations no longer needed to be listed as endangered or threatened. And of the remaining five groups four continue to be listed as endangered and one is listed as threatened. (See map below)

Nature and wildlife are inherently resilient. Sometimes all they need is for humans to step aside.

Ongoing and emerging threats to humpback whales include entanglement in fishing gear and vessel collision. Noise from gas and oil drilling can interfere with their hearing and ability to communicate and climate change poses a threat to their prey

Exception To Whale Hunting: Some exceptions to whale hunting are granted to indigenous people under the IWC. Whale hunting for indigenous groups is a way of life and a means to subsistence and not a means to profit from. Read more

Countries In Violation Of the IWC Ban: Japan, Iceland and Norway have failed to comply with the IWC ban set forth in 1986 and continue to practice commercial whaling..

Did you know?

Humpback whales are both compassionate and altruistic!

Smithsonian

What Humpback Whales Can Teach Us About Compassion

Habitat: Humpback whales are found in most oceans throughout the world and they have been divided into 14 distinct populations. These toothless gentle giants are among the largest creatures of the ocean even though their diet consists of some of the tiniest marine life, such as krill and small schooling fish. They migrate seasonally to warmer waters to breed and calve and return to cooler waters during the summer months, where their prey is plentiful. The vast distances they travel between their breeding and feeding grounds makes these among the longest migrations undertaken by any sea mammals. Some humpbacks have been known to travel up to 5,000 miles every year.

.

Threats: Commercial whaling started in the 1700s. Humpback whales were primarily hunted for blubber and whale oil, both of which were used as lubricants and fuel for lighting lamps. Whale oil was refined and used to make other products such as soaps and candles. Given how predictable the migratory patterns of humpback whales are, hunting boats showed up in the same locations year after year. The indiscriminate killing of whales for almost two centuries reduced their population from their historic stocks which numbered in the tens of thousands to just a few hundred by 1985 and put the species at risk of extinction.

Protective Status: All humpback whales were listed as endangered in 1970. Of the 14 distinct populations, four are still listed as endangered and one is listed as threatened.(See map below)

Recovery: When the devastating impact of commercial whaling became apparent, countries around the world started imposing bans on commercial whaling. Eventually, a global moratorium on whale hunting was put into effect in 1986 by the International Whaling Commission (IWC). The ban provided the much-needed respite for the humpback whales and their numbers have since bounced back. While it is hard to count the exact number of whales within each of these 14 distinct populations, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) 2016 stock assessment reports provided a close approximate. NOAA estimated that 12 of those populations had more than 2,000 humpback whales each and two populations had fewer than 2,000. The humpback whale populations that live off the east and west coast of Australia boast numbers in the upward of 20,000 while the smallest known population which lives in the Arabian Sea is believed to have as few as 80 individuals.

In 2016, as a result of the successful recovery of the humpback whales, NOAA announced that 9 populations no longer needed to be listed as endangered or threatened. And of the remaining five groups four continue to be listed as endangered and one is listed as threatened. (See map below)

Nature and wildlife are inherently resilient. Sometimes all they need is for humans to step aside.

Ongoing and emerging threats to humpback whales include entanglement in fishing gear and vessel collision. Noise from gas and oil drilling can interfere with their hearing and ability to communicate and climate change poses a threat to their prey

Exception To Whale Hunting: Some exceptions to whale hunting are granted to indigenous people under the IWC. Whale hunting for indigenous groups is a way of life and a means to subsistence and not a means to profit from. Read more

Countries In Violation Of the IWC Ban: Japan, Iceland and Norway have failed to comply with the IWC ban set forth in 1986 and continue to practice commercial whaling..

Did you know?

Humpback whales are both compassionate and altruistic!

Smithsonian

What Humpback Whales Can Teach Us About Compassion

Map showing locations of the 14 distinct populations of humpback whales worldwide.

Source: NOAA

Source: NOAA

Additional Species That Have Recovered

Along with the four species featured in this edition there are others that conservationists have successfully helped recover from the brink of extinction. A small sampling of those species are listed below.

|

National Geographic: Follow this link to learn more about these species

|

Wildlife Conservation Society: Follow this link to learn about some of these species

|

Who to support:

Please find listed below organizations that are working tirelessly to protect the Kihansi spray toad, the Tennessee purple cone flower, the tiger and the humpback whale. Follow their links to learn more about their work and the species they protect. Please consider supporting their cause by making a donation, signing petitions, volunteering, learning about their work and educating others.

Please find listed below organizations that are working tirelessly to protect the Kihansi spray toad, the Tennessee purple cone flower, the tiger and the humpback whale. Follow their links to learn more about their work and the species they protect. Please consider supporting their cause by making a donation, signing petitions, volunteering, learning about their work and educating others.

|

Kihansi spry toad

Toledo Zoo Bronx Zoo Tennessee purple coneflower Tennessee Nature Conservancy Center for Cedar Glades Studies Humpback whale American Cetacean Society National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’ Wildlife Conservation Society World Wildlife Fund |

Tiger

Panthera Wildlife Protection Society of India Tambling Nature Conservation Rimba Save the Tiger Fund (Now partnered with Panthera), World Wildlife Funds Wildlife Conservation Society National Geographic - The Big Cat Initiative You may also choose to contribute to tiger conservation by buying this beautiful coffee table book for yourself or as a gift. Tigers Forever - Saving the worlds most endangered big cat By Steve Winter and Sharon Guynup. You can read the description of the book and buy it at the National Geographic store or at Amazon. Part of the proceeds from the book sale will go to Panthera’s Tigers Forever program. |