In Spotlight: Monarch Butterfly

|

Last October, I spotted monarch caterpillars and a chrysalis for the first time in my garden. Watching this metamorphosis unfold only 10 feet from my front door was incredibly captivating. The day the butterfly emerged and flew away, I looked up the distance between my house and the butterfly's overwintering grounds in Michoacán, Mexico. The distance is 1790 miles one way. As I marveled at the solo expedition the butterfly had just undertaken, I imagined taking a road trip with it. I thought about what I would need to complete this journey and made my imaginary checklist. I wondered how easy or difficult my trip would be if I did not have access to these resources on my list? What would I do if there were no restaurants to eat at, rest areas to stop, or gas stations to refuel? Like me, the butterfly that left my garden also needs resources like food, water, and shelter to complete its 3,000-mile migration successfully. But are these resources secure or disrupted for the butterfly?

I recently interviewed Susan Meyers, an educator, trainer, and a volunteer with Monarchs Across Georgia, Environmental Education Alliance, to find out how the butterflies were doing in the wild? We had a fascinating conversation about the monarch's epic migration, built-in GPS, and defenses against predators. Please join me as we take flight with the butterflies on their annual migration across three countries. The interview is divided into three segments: - Introduction and interesting facts - Migration - Conservation Included below are the highlights of the interview. It has been edited and condensed for clarity. |

Did you know......

"A group of monarch butterflies is called a flutter."

- Public Broadcasting Services

"A group of monarch butterflies is called a flutter."

- Public Broadcasting Services

Susan Meyers

Interviewee

Ayesha Siraj

Interviewer

Interviewee

Ayesha Siraj

Interviewer

Introduction And Interesting Facts

Ayesha: How many species of monarch butterflies are around the globe?

Susan: Monarch is the common name for a particular butterfly species, Danaus plexippus, found on the North American continent. Worldwide there might be some commonly named butterflies like the African monarch or the southern monarch that might have monarch in their common name, but they're not Danaus plexippus. There are three sub species of the Danaus plexippus - the Danaus plexippus plexippus, Danaus plexippus megalippe, Danaus plexippus nigrippus.

Ayesha: Is the North American continent the Danaus plexippus' home range?

Susan: Yes, North America is their primary range. But they extend into the Caribbean islands, Central America, and the northern part of South America. Amazingly they are also found in Hawaii, parts of Australia, and the nearby islands. There is a little colony that has been documented in Europe as well. While it is interesting that they are found in all these countries, we don't know exactly how they got there.

There are several theories on how these butterflies spread to various parts of the world. One explanation is that they were on plants as eggs and caterpillars when those plants were transported to those countries. However, to get to Hawaii, perhaps there was some direct help from humans. It is possible that someone liked the beautiful butterfly and decided to take it with them.

Ayesha: How many populations of monarchs are found in North America?

Susan: There are three populations of monarchs in North America. The eastern population is to the east of the Rocky Mountains, the western population is west of the Rocky Mountains, and the Florida population is in southern Florida. The Florida population is resident. Not all the butterflies in the eastern population get down to Mexico; some may go down to Florida or the Caribbean islands and become residents there. The grand migration is really from the eastern population.

Ayesha: The monarchs are well known for their annual migration in the US and Mexico. Do the populations in other parts of the world migrate, or are they resident populations in those regions?

Susan: The populations around the world are resident species, although there is some movement during the season because of food availability or weather. If it gets really dry in one area, they might move to another area where there are more nectar sources. But the grand migration is only on the North American continent.

Susan: Monarch is the common name for a particular butterfly species, Danaus plexippus, found on the North American continent. Worldwide there might be some commonly named butterflies like the African monarch or the southern monarch that might have monarch in their common name, but they're not Danaus plexippus. There are three sub species of the Danaus plexippus - the Danaus plexippus plexippus, Danaus plexippus megalippe, Danaus plexippus nigrippus.

Ayesha: Is the North American continent the Danaus plexippus' home range?

Susan: Yes, North America is their primary range. But they extend into the Caribbean islands, Central America, and the northern part of South America. Amazingly they are also found in Hawaii, parts of Australia, and the nearby islands. There is a little colony that has been documented in Europe as well. While it is interesting that they are found in all these countries, we don't know exactly how they got there.

There are several theories on how these butterflies spread to various parts of the world. One explanation is that they were on plants as eggs and caterpillars when those plants were transported to those countries. However, to get to Hawaii, perhaps there was some direct help from humans. It is possible that someone liked the beautiful butterfly and decided to take it with them.

Ayesha: How many populations of monarchs are found in North America?

Susan: There are three populations of monarchs in North America. The eastern population is to the east of the Rocky Mountains, the western population is west of the Rocky Mountains, and the Florida population is in southern Florida. The Florida population is resident. Not all the butterflies in the eastern population get down to Mexico; some may go down to Florida or the Caribbean islands and become residents there. The grand migration is really from the eastern population.

Ayesha: The monarchs are well known for their annual migration in the US and Mexico. Do the populations in other parts of the world migrate, or are they resident populations in those regions?

Susan: The populations around the world are resident species, although there is some movement during the season because of food availability or weather. If it gets really dry in one area, they might move to another area where there are more nectar sources. But the grand migration is only on the North American continent.

|

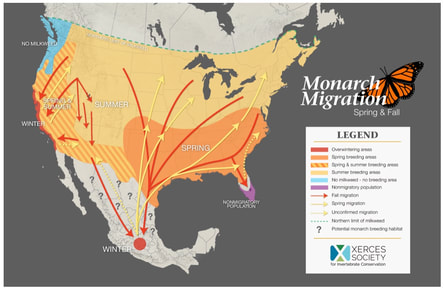

Ayesha: What is the migration route of the eastern and western populations, and where do they migrate to?

Susan: The eastern population essentially has two routes as they migrate southward, the central corridor or I-35, and the coastal route. Their destination is the Transvolcanic Mountains, west of Mexico City at the border between the states of Mexico and Michoacan. The north-bound or spring migration route is completed by several generations, so it is difficult to know the exact route. By late March, sightings (on the Journey North map) are in Texas and the southeast. In April, the first generation has moved further north into Oklahoma, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina. By May, there are sightings as far north as Toronto, Canada. There is no specific route of the western population. They head to the California coast. |

Ayesha: What is the wingspan of the monarch, and what do they weigh?

Susan: The monarch wingspan measures about 4-5 inches. The wing length is measured from the body to the apex of the fore wing. On average, each wing is about 2- 2.5 inches wide. The male butterflies are slightly larger than the females.

The monarch weighs around half a gram. It is about the weight of a paperclip.

Ayesha: What is the difference between a male and a female butterfly?

Susan: If you look at the veins on the male butterfly's hind wings, you will notice black dots called androconial sacs that hold pheromones to attract females. The females don't have androconial sacs. Although the males can produce pheromones, they do not require them for successful mating.

Another differentiating characteristic is the width of the veins. It is not easy to see the difference if you have only one butterfly. But if you have a male and a female side by side, you will notice the veins in the females appear to be wider than the males. This gives them a more muted appearance. Since she is the one with the eggs, she wants to be subdued in coloration so she can be concealed. As with all animal species, the male is flashier.

Finally, if you look at their abdomen, the males have claspers on their abdomen for holding on to the females. And the females have a slit on the underside of their abdomen. This is hard to see if they are sitting on a flower. But the dots and the veins are easy to identify.

Susan: The monarch wingspan measures about 4-5 inches. The wing length is measured from the body to the apex of the fore wing. On average, each wing is about 2- 2.5 inches wide. The male butterflies are slightly larger than the females.

The monarch weighs around half a gram. It is about the weight of a paperclip.

Ayesha: What is the difference between a male and a female butterfly?

Susan: If you look at the veins on the male butterfly's hind wings, you will notice black dots called androconial sacs that hold pheromones to attract females. The females don't have androconial sacs. Although the males can produce pheromones, they do not require them for successful mating.

Another differentiating characteristic is the width of the veins. It is not easy to see the difference if you have only one butterfly. But if you have a male and a female side by side, you will notice the veins in the females appear to be wider than the males. This gives them a more muted appearance. Since she is the one with the eggs, she wants to be subdued in coloration so she can be concealed. As with all animal species, the male is flashier.

Finally, if you look at their abdomen, the males have claspers on their abdomen for holding on to the females. And the females have a slit on the underside of their abdomen. This is hard to see if they are sitting on a flower. But the dots and the veins are easy to identify.

|

Male Monarch Butterfly

Photo Credit: Susan Meyers |

Female Monarch Butterfly

Photo Credit: Susan Meyers |

Ayesha: What are the various stages of their lifecycle?

Susan: The different stages are egg, larva/caterpillar, chrysalis, and adult butterfly.

The egg stage lasts between 3 to 5 days, depending on the temperature. The warmer the temperature, the faster the lifecycle goes. The egg darkens at the top before the caterpillar chews its way out. That dark spot is the caterpillar's big black head. The newly hatched caterpillar is light gray with no striping. It gets its distinctive black striping once it starts eating the milkweed. It increases 2000 times in its mass from the first instar to the fifth instar. Typically, one caterpillar eats about 30 milkweed leaves which is almost the entire plant.

Before I explain the next stage, let me explain what an instar is. For the caterpillar to get larger, it must shed its exoskeleton. Instar is the stage of the larva in between the shedding of the exoskeleton. Finally, they crawl away from the milkweed at the fifth instar to create their chrysalis. They spin a silk pad and hang upside down from a leaf for 12 hours or more. During this time, they split the exoskeleton for the last time and wiggle out of it to drop it. They don't want the exoskeleton to be lying against the chrysalis because it can cause a deformity.

Once the exoskeleton is dropped, a black stick-like appendage called the cremaster plugs and twists into the silk pad. At that very moment, the caterpillar lets go with its anal legs. It's a lot of work that a little caterpillar goes through to move to its next stage of metamorphosis.

The chrysalis looks a little soft and mushy. It's a little bit like the shape of the caterpillar itself, then it hardens up in a few hours. You can see the abdominal segments, you can already see the wings, and if we flip it over, you can see the lines that'll become the legs and the proboscis. The pupa or chrysalis stage lasts about 8 to 14 days. Then it turns dark and looks black, but if you look closer, you can see the color of the butterfly. That's the last thing that happens before the butterfly emerges from the chrysalis or a "ecloses" that's the scientific term for it. The chrysalis splits open, and the butterfly comes out head first. Its wings are crumpled and wet, and its abdomen is expanded with fluid. It pumps this fluid into the wings to expand them, and then in a few hours, the wings are dry enough for it to fly.

Susan: The different stages are egg, larva/caterpillar, chrysalis, and adult butterfly.

The egg stage lasts between 3 to 5 days, depending on the temperature. The warmer the temperature, the faster the lifecycle goes. The egg darkens at the top before the caterpillar chews its way out. That dark spot is the caterpillar's big black head. The newly hatched caterpillar is light gray with no striping. It gets its distinctive black striping once it starts eating the milkweed. It increases 2000 times in its mass from the first instar to the fifth instar. Typically, one caterpillar eats about 30 milkweed leaves which is almost the entire plant.

Before I explain the next stage, let me explain what an instar is. For the caterpillar to get larger, it must shed its exoskeleton. Instar is the stage of the larva in between the shedding of the exoskeleton. Finally, they crawl away from the milkweed at the fifth instar to create their chrysalis. They spin a silk pad and hang upside down from a leaf for 12 hours or more. During this time, they split the exoskeleton for the last time and wiggle out of it to drop it. They don't want the exoskeleton to be lying against the chrysalis because it can cause a deformity.

Once the exoskeleton is dropped, a black stick-like appendage called the cremaster plugs and twists into the silk pad. At that very moment, the caterpillar lets go with its anal legs. It's a lot of work that a little caterpillar goes through to move to its next stage of metamorphosis.

The chrysalis looks a little soft and mushy. It's a little bit like the shape of the caterpillar itself, then it hardens up in a few hours. You can see the abdominal segments, you can already see the wings, and if we flip it over, you can see the lines that'll become the legs and the proboscis. The pupa or chrysalis stage lasts about 8 to 14 days. Then it turns dark and looks black, but if you look closer, you can see the color of the butterfly. That's the last thing that happens before the butterfly emerges from the chrysalis or a "ecloses" that's the scientific term for it. The chrysalis splits open, and the butterfly comes out head first. Its wings are crumpled and wet, and its abdomen is expanded with fluid. It pumps this fluid into the wings to expand them, and then in a few hours, the wings are dry enough for it to fly.

Click on the image to enlarge and read description

Photo credit: Susan Meyers (Image 1,2 &3)

Photo credit: Ayesha Siraj (Image 4 & 6)

Photo credit: Pixabay (Image 5)

Photo credit: Susan Meyers (Image 1,2 &3)

Photo credit: Ayesha Siraj (Image 4 & 6)

Photo credit: Pixabay (Image 5)

Ayesha: You mentioned that the monarch caterpillar could eat up to 30 leaves. Can you tell us about the dependency of the monarch caterpillar on the milkweed?

Susan: Some butterflies have multiple host plants to lay their eggs on. For example, a black swallowtail butterfly can choose to lay her eggs on plants like carrot, dill, parsley, fennel, etc. And its caterpillar will eat these host plant leaves.

But the monarch caterpillar is restricted. It can only eat milkweed leaves. Hence, the monarch butterfly will only lay her eggs on milkweed, Asclepias species. In Georgia, there are 22 native species of milkweed. When planting milkweed, one needs to make sure that we are using a native milkweed species appropriate to your ecoregion.

Ayesha: I am glad you brought up native milkweed. When researching native plants and milkweed species for my pollinator garden, one of the articles I read recommended not using the Mexican milkweed? Why is that?

Susan: You're referring to Asclepias curassavica. It's commonly known as tropical milkweed, Mexican milkweed, or blood flower. It is all over Florida, in coastal areas of North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and the Gulf of Mexico. It is not native to these regions; however, it is sold quite a bit in nurseries. I'm familiar with the research done by the University of Georgia on this milkweed species, which found that it is flourishing in gardens and has escaped into the wild.

So why shouldn't we plant this milkweed in our garden? Because it impacts migration.

Our native milkweed being perennial, dies back for the winter. But the Mexican milkweed can exist during winter unless we have a hard freeze. So instead of heading to Mexico, the monarchs may stop to lay eggs on the Mexican milkweed because it is not senescing (deteriorating with age) as our natives are.

The monarchs go down to Mexico to avoid extended periods of freezing temperature. But if they stop to nectar and lay eggs on the Mexican milkweed, it is a problem. Because this is the only milkweed species available during winters, the caterpillars might eat it all before they get to the chrysalis stage. If that happens, they may starve to death. Or they could freeze to death if there is a hard freeze.

There is another interesting research by Dara Satterfield which found that a large number of butterflies that are overwintering in the coastal states on tropical milkweed were infected with a protozoan parasite called Ophryocystis elektroscirrha (OE). The parasite is now being studied through UGA through Project Monarch Health at the Odum School of Ecology. Their research found that the Western population is about 30% infected, the population in southern Florida is 85 to 90% infected, and the eastern population is less than 10% infected. They believe that the eastern population is less infected because this parasite weakens the butterfly, so they cannot make that long migration. In other words, they are culled out of the population. This is an emerging threat that is being studied.

Chattahoochee Nature Center and Georgia Plant Conservation Alliance

Xerces Society

Ayesha: Who are the monarch's natural predators, and what is the survival rate of the butterfly as it goes through its different stages of lifecycle?

Susan: When the Monarch caterpillar eats the milkweed, it sequesters a toxin from the leaf of the milkweed. That toxin is a cardiac glycoside which essentially makes the monarch in its larva and adult stage distasteful to vertebrate predators. There is a great video that Dr. Lincoln Brower made where he fed a blue jay a monarch butterfly, and then a few minutes later, the blue jay started throwing up . Once a bird, or in this case, the blue jay, has had the negative experience of vomiting, it learns to avoid any butterfly that has the orange, black coloration like the monarch in the future. (Article: The Case Of The Barfing Blue Jay)

Vertebrate predators are not a significant problem for the monarchs in the United States. However, invertebrate predators are a big problem. Spiders and ants usually consume eggs. Wasps, stink bugs, assassin bugs, and several other invertebrates consume the monarch larva.

Only about 5% of eggs will make it to the 5th instar stage.

Ayesha: In the web of life, nature creates perfect checks and balances through prey-predation relationships. Newborns are especially vulnerable to predation and the elements, yet a small percentage makes it to adult life, which is remarkable. How many eggs does one butterfly lay, and what is 5% of that?

Susan: The female lays about 500 eggs. So only 25 eggs will make it to the fifth instar phase. In other words, for every butterfly, only 25 butterflies will emerge.

Ayesha: Since you have been to the state of Michoacán in Mexico, I would love to hear your description of the monarch's overwintering grounds.

Susan: I went for the first time in 2003 with Dr. Bill Calvert. He is among the first few biologists who studied the monarchs in Mexico. I had seen pictures and heard stories from acquaintances, and I had always wanted to visit the colony. So, I signed up with teachers from New Jersey and Dr. Calvert to visit the butterflies that year.

Walking into the forest for the first time was spectacular; the forest had these huge trees! We had to ride on horseback for an hour and then walk into the forest for another hour. We were at 10,000 feet, and being lowlanders, we were stopping every so often to catch our breath. We went in February, and they were wildflowers growing everywhere, reds, yellows, pinks, and purples. It was just beautiful! And then we arrived at the colony. And I was looking around thinking, wow, there are lots of leaves still on the trees. And then Dr. Calvert said, "Susan, these are evergreen trees and what you're seeing are the monarch butterflies hanging onto the needles." And then we started seeing the clumps. It's almost like beehives dripping from branches. It is absolutely spectacular! The butterflies tend to go to the same trees every year. But different things happen that make every year feel different. Sometimes the weather is a little different, or the number of butterflies is different. In any case, I love seeing the butterflies. The experience is magical and spiritual all at the same time. One of my favorite ways to experience the butterflies is to lay down on the trail and watch them stream over you. You might think you can't hear a butterfly, but when you have hundreds flying over you, it sounds like soft rain.

After I went to Mexico that year, I decided that it would be an annual migration for me too. So, the following year I organized a group of Georgia teachers to travel to Mexico. And probably for eight or 10-years, I either led or co-led a trip with Dr. Calvert. But the best part of my subsequent trips is to watch the faces of people who see the butterflies for the first time. That is one of the reasons why I do that.

Susan: Some butterflies have multiple host plants to lay their eggs on. For example, a black swallowtail butterfly can choose to lay her eggs on plants like carrot, dill, parsley, fennel, etc. And its caterpillar will eat these host plant leaves.

But the monarch caterpillar is restricted. It can only eat milkweed leaves. Hence, the monarch butterfly will only lay her eggs on milkweed, Asclepias species. In Georgia, there are 22 native species of milkweed. When planting milkweed, one needs to make sure that we are using a native milkweed species appropriate to your ecoregion.

Ayesha: I am glad you brought up native milkweed. When researching native plants and milkweed species for my pollinator garden, one of the articles I read recommended not using the Mexican milkweed? Why is that?

Susan: You're referring to Asclepias curassavica. It's commonly known as tropical milkweed, Mexican milkweed, or blood flower. It is all over Florida, in coastal areas of North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and the Gulf of Mexico. It is not native to these regions; however, it is sold quite a bit in nurseries. I'm familiar with the research done by the University of Georgia on this milkweed species, which found that it is flourishing in gardens and has escaped into the wild.

So why shouldn't we plant this milkweed in our garden? Because it impacts migration.

Our native milkweed being perennial, dies back for the winter. But the Mexican milkweed can exist during winter unless we have a hard freeze. So instead of heading to Mexico, the monarchs may stop to lay eggs on the Mexican milkweed because it is not senescing (deteriorating with age) as our natives are.

The monarchs go down to Mexico to avoid extended periods of freezing temperature. But if they stop to nectar and lay eggs on the Mexican milkweed, it is a problem. Because this is the only milkweed species available during winters, the caterpillars might eat it all before they get to the chrysalis stage. If that happens, they may starve to death. Or they could freeze to death if there is a hard freeze.

There is another interesting research by Dara Satterfield which found that a large number of butterflies that are overwintering in the coastal states on tropical milkweed were infected with a protozoan parasite called Ophryocystis elektroscirrha (OE). The parasite is now being studied through UGA through Project Monarch Health at the Odum School of Ecology. Their research found that the Western population is about 30% infected, the population in southern Florida is 85 to 90% infected, and the eastern population is less than 10% infected. They believe that the eastern population is less infected because this parasite weakens the butterfly, so they cannot make that long migration. In other words, they are culled out of the population. This is an emerging threat that is being studied.

Chattahoochee Nature Center and Georgia Plant Conservation Alliance

Xerces Society

Ayesha: Who are the monarch's natural predators, and what is the survival rate of the butterfly as it goes through its different stages of lifecycle?

Susan: When the Monarch caterpillar eats the milkweed, it sequesters a toxin from the leaf of the milkweed. That toxin is a cardiac glycoside which essentially makes the monarch in its larva and adult stage distasteful to vertebrate predators. There is a great video that Dr. Lincoln Brower made where he fed a blue jay a monarch butterfly, and then a few minutes later, the blue jay started throwing up . Once a bird, or in this case, the blue jay, has had the negative experience of vomiting, it learns to avoid any butterfly that has the orange, black coloration like the monarch in the future. (Article: The Case Of The Barfing Blue Jay)

Vertebrate predators are not a significant problem for the monarchs in the United States. However, invertebrate predators are a big problem. Spiders and ants usually consume eggs. Wasps, stink bugs, assassin bugs, and several other invertebrates consume the monarch larva.

Only about 5% of eggs will make it to the 5th instar stage.

Ayesha: In the web of life, nature creates perfect checks and balances through prey-predation relationships. Newborns are especially vulnerable to predation and the elements, yet a small percentage makes it to adult life, which is remarkable. How many eggs does one butterfly lay, and what is 5% of that?

Susan: The female lays about 500 eggs. So only 25 eggs will make it to the fifth instar phase. In other words, for every butterfly, only 25 butterflies will emerge.

Ayesha: Since you have been to the state of Michoacán in Mexico, I would love to hear your description of the monarch's overwintering grounds.

Susan: I went for the first time in 2003 with Dr. Bill Calvert. He is among the first few biologists who studied the monarchs in Mexico. I had seen pictures and heard stories from acquaintances, and I had always wanted to visit the colony. So, I signed up with teachers from New Jersey and Dr. Calvert to visit the butterflies that year.

Walking into the forest for the first time was spectacular; the forest had these huge trees! We had to ride on horseback for an hour and then walk into the forest for another hour. We were at 10,000 feet, and being lowlanders, we were stopping every so often to catch our breath. We went in February, and they were wildflowers growing everywhere, reds, yellows, pinks, and purples. It was just beautiful! And then we arrived at the colony. And I was looking around thinking, wow, there are lots of leaves still on the trees. And then Dr. Calvert said, "Susan, these are evergreen trees and what you're seeing are the monarch butterflies hanging onto the needles." And then we started seeing the clumps. It's almost like beehives dripping from branches. It is absolutely spectacular! The butterflies tend to go to the same trees every year. But different things happen that make every year feel different. Sometimes the weather is a little different, or the number of butterflies is different. In any case, I love seeing the butterflies. The experience is magical and spiritual all at the same time. One of my favorite ways to experience the butterflies is to lay down on the trail and watch them stream over you. You might think you can't hear a butterfly, but when you have hundreds flying over you, it sounds like soft rain.

After I went to Mexico that year, I decided that it would be an annual migration for me too. So, the following year I organized a group of Georgia teachers to travel to Mexico. And probably for eight or 10-years, I either led or co-led a trip with Dr. Calvert. But the best part of my subsequent trips is to watch the faces of people who see the butterflies for the first time. That is one of the reasons why I do that.

Migration

Ayesha: Why do the monarchs migrate?

Susan: The monarch butterfly nectars off a variety of flowers. They don't necessarily need the milkweed for their sustenance, but they need it as the host plant for their caterpillar. When the host plant and the nectar plants die back for the winter, the butterflies need to move. Every animal has some winter strategy. Bears hibernate, different butterflies have strategies to survive the winter. For example, they may overwinter as eggs, larva, or chrysalis. The monarch butterfly, however, overwinters as an adult. And because they cannot withstand extended periods of freezing temperature, they head south to Mexico to their overwintering grounds.

All winter, they are sedentary and exist off their fat stores. The few times they move is when they need to hydrate themselves. They do so by going down to mountain streams within the sanctuary.

But when spring arrives, they are looking for nectar to drink and milkweed to lay their eggs on. There aren't enough nectar plants or milkweed in Mexico for the millions of monarchs there. Hence, they trek north, and that begins their migration.

If you want to watch the migration, you can follow a free citizen science project called Journey North. It is very easy for people to be involved. The project allows citizens to log their sightings of monarchs. Each sighting is marked by a dot on the map. If you click on the dot, it brings up the actual location of the sighting. The person making the entry can attach a picture of the butterfly and add additional details in the comment box. Someone interested in learning more about the sighting can query through the Journey North website to the person who logged the sighting.

Ayesha: Is there a way to track the butterflies in real-time?

Susan: There is ongoing research on ways to attach a transmitter on individual butterflies to track them, but the technology doesn't exist yet.

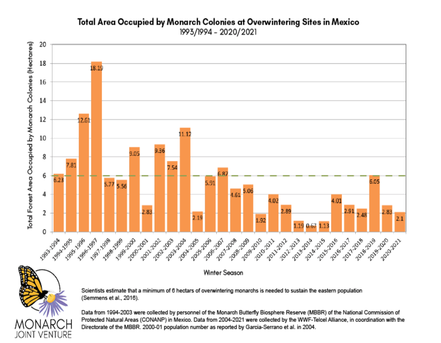

Ayesha: How do they count how many butterflies make it to Mexico every year?

Susan: We don't have a formula to count them precisely. The butterflies are estimated by the number of hectares occupied by the colony. That said, it's hard to count a hectare of butterflies. Depending on how loosely or densely packed they are, they are usually probably around 25 or 30 million butterflies per hectare.

Ayesha: When do the monarchs start migrating north? How do they know it is time?

Susan: Monarchs usually leave Mexico by mid-March. Research seems to indicate that temperature, the number of cold days in Mexico, is critical for the northward migration. It triggers their reversal flight direction.

Ayesha: It is my understanding that one butterfly does not complete the entire migration. Can you elaborate on how many generations it takes to complete this migration?

Susan: We start with what we call the first generation. The first generation is the eggs laid by the female butterfly that spent all winter in Mexico. The eggs are laid either in Texas or Louisiana. Some make it as far as Georgia. We know this is the first generation because of their tattered wings and the time of the year.

It takes about a month, perhaps a little longer, for that first generation to become an adult butterfly and move further north. They're moving north looking for milkweed. The milkweed in the southern states comes out of the ground first because we have warmer temperatures. And as it warms up across the country northward, the butterfly moves northward following the milkweed. By then, it is the second or third generation. The butterflies born in the spring and summer live only about 4 to 6 weeks. But the butterflies that emerge from the chrysalis in late summer or as late as September are the fourth and final generation. They are called the Methuselah generation and they can live unto 9 months. They are affected by environmental cues like shortening days, cooler temperatures, the senescence of the nectar and host plants. Unlike the first three generations, the fourth generation is not sexually mature when they emerge. They are in reproductive diapause. They're not going to mate, but they're going to migrate.

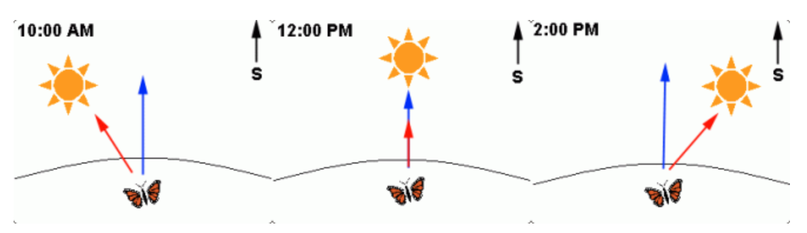

Given that they were born somewhere between Canada and Texas, how do they know where to go? They use their circadian clock and a sun compass that is built in their antenna. They can orient to the sun with their antennae. If it is 10 in the morning, they will fly to the west of the sun, maintaining a southwestward flight path. If it's noon, they will fly straight towards the sun. If it is 2:00 pm, they will fly east to the sun. So, they're always on the same path. They will orient themselves as to how the antenna is perceiving the sun.

Susan: The monarch butterfly nectars off a variety of flowers. They don't necessarily need the milkweed for their sustenance, but they need it as the host plant for their caterpillar. When the host plant and the nectar plants die back for the winter, the butterflies need to move. Every animal has some winter strategy. Bears hibernate, different butterflies have strategies to survive the winter. For example, they may overwinter as eggs, larva, or chrysalis. The monarch butterfly, however, overwinters as an adult. And because they cannot withstand extended periods of freezing temperature, they head south to Mexico to their overwintering grounds.

All winter, they are sedentary and exist off their fat stores. The few times they move is when they need to hydrate themselves. They do so by going down to mountain streams within the sanctuary.

But when spring arrives, they are looking for nectar to drink and milkweed to lay their eggs on. There aren't enough nectar plants or milkweed in Mexico for the millions of monarchs there. Hence, they trek north, and that begins their migration.

If you want to watch the migration, you can follow a free citizen science project called Journey North. It is very easy for people to be involved. The project allows citizens to log their sightings of monarchs. Each sighting is marked by a dot on the map. If you click on the dot, it brings up the actual location of the sighting. The person making the entry can attach a picture of the butterfly and add additional details in the comment box. Someone interested in learning more about the sighting can query through the Journey North website to the person who logged the sighting.

Ayesha: Is there a way to track the butterflies in real-time?

Susan: There is ongoing research on ways to attach a transmitter on individual butterflies to track them, but the technology doesn't exist yet.

Ayesha: How do they count how many butterflies make it to Mexico every year?

Susan: We don't have a formula to count them precisely. The butterflies are estimated by the number of hectares occupied by the colony. That said, it's hard to count a hectare of butterflies. Depending on how loosely or densely packed they are, they are usually probably around 25 or 30 million butterflies per hectare.

Ayesha: When do the monarchs start migrating north? How do they know it is time?

Susan: Monarchs usually leave Mexico by mid-March. Research seems to indicate that temperature, the number of cold days in Mexico, is critical for the northward migration. It triggers their reversal flight direction.

Ayesha: It is my understanding that one butterfly does not complete the entire migration. Can you elaborate on how many generations it takes to complete this migration?

Susan: We start with what we call the first generation. The first generation is the eggs laid by the female butterfly that spent all winter in Mexico. The eggs are laid either in Texas or Louisiana. Some make it as far as Georgia. We know this is the first generation because of their tattered wings and the time of the year.

It takes about a month, perhaps a little longer, for that first generation to become an adult butterfly and move further north. They're moving north looking for milkweed. The milkweed in the southern states comes out of the ground first because we have warmer temperatures. And as it warms up across the country northward, the butterfly moves northward following the milkweed. By then, it is the second or third generation. The butterflies born in the spring and summer live only about 4 to 6 weeks. But the butterflies that emerge from the chrysalis in late summer or as late as September are the fourth and final generation. They are called the Methuselah generation and they can live unto 9 months. They are affected by environmental cues like shortening days, cooler temperatures, the senescence of the nectar and host plants. Unlike the first three generations, the fourth generation is not sexually mature when they emerge. They are in reproductive diapause. They're not going to mate, but they're going to migrate.

Given that they were born somewhere between Canada and Texas, how do they know where to go? They use their circadian clock and a sun compass that is built in their antenna. They can orient to the sun with their antennae. If it is 10 in the morning, they will fly to the west of the sun, maintaining a southwestward flight path. If it's noon, they will fly straight towards the sun. If it is 2:00 pm, they will fly east to the sun. So, they're always on the same path. They will orient themselves as to how the antenna is perceiving the sun.

Source: Monarch Joint Venture

There are several scientific studies in which they have removed the antenna, and in those cases, the butterflies have no directional flight. They have also conducted experiments in which they have painted the antennae with clear nail polish or black nail polish. The study found that they can orient themselves to the sun with one antenna or when the antennae are painted with clear nail polish. If both antennae are painted black or removed, they cannot orient to the sun because their antennae are their sensor. They believe that the butterflies can use landscape for direction just like birds do.

The butterflies start funneling as they come into Texas. Then they come down to the mountain range of Sierra Madre and stop at the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt. It is at that point where the angle of the sun drops below 57 degrees, and they just know that they need to stop there.

Ayesha: I was reading about the mystery behind the migration of the painted lady butterfly in the United Kingdom. Researchers could not determine if or where the painted lady butterfly was migrating to because they didn't have any visual sighting of them flying away in the fall. They recently solved the mystery by using radar imaging which suggested that the butterflies fly out of view at very high altitudes. I am curious if monarchs fly at high altitudes too?

Susan: Monarchs can fly high. If you have ever watched and compared butterflies' flights, you will notice that most butterflies flutter their wings. But the monarch flaps and glides. So that's a distinctive flight pattern of the monarch, which allows it to get to higher altitudes where it can catch wind currents to help it travel further.

Ayesha: What is the total number of miles they cover during their migration?

Susan: We can only calculate the distance based on where a butterfly was tagged and where it ended up in Mexico. That's the only scientific data we have. It is highly unlikely that a butterfly that was tagged on its way to Mexico will be found on its migration north come spring. But since we know that the generation that flies to Mexico has to fly at least part of the way back, some butterflies fly between 2500 -3000 miles. That is the whole idea of migration versus immigration. Immigration is one way, and migration is two-way.

Ayesha: So one little butterfly with a wingspan of 4-5 inches can fly up to 3,000 miles?

Susan: Yes, it can be that far.

Ayesha: Do we know how many miles they cover in a day?

Susan: They travel about 25 to 30 miles per day unless they catch the tailwind. One butterfly was documented to have traveled 265 miles. The reason we know that is because it was tagged, and then it was found the same day further south in the United States. The person captured the butterfly, read the tag, and estimated the distance. It was interesting because there aren't that many recoveries of tags within the United States. Most of the recoveries are down in Mexico.

Ayesha: Why aren't tags recovered in the United States? Do the butterflies not come down to forage?

Susan: Yes, they come down to nectar. It's incredibly important that the butterflies have enough nectar sources on their migration route. Unlike the hummingbirds that lose weight, the monarch must gain weight on their migration south to build up enough fat reserves to last all winter in Mexico. So, they need to nectar on their migration.

The reason fewer tags are recovered in the United States is that only about 100,000 butterflies are tagged each year, but millions of butterflies travel to Mexico across the eastern United States. What are the chances of finding one in such a large area? However, since all of them overwinter in a few hectares in Mexico, the probability of finding one that is tagged increases significantly.

Ayesha: Are there any specific conditions under which the butterflies don't fly?

Susan: Butterflies don't fly at night, when it's raining, or when there are strong winds. They find shelter under these conditions. 2

The butterflies start funneling as they come into Texas. Then they come down to the mountain range of Sierra Madre and stop at the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt. It is at that point where the angle of the sun drops below 57 degrees, and they just know that they need to stop there.

Ayesha: I was reading about the mystery behind the migration of the painted lady butterfly in the United Kingdom. Researchers could not determine if or where the painted lady butterfly was migrating to because they didn't have any visual sighting of them flying away in the fall. They recently solved the mystery by using radar imaging which suggested that the butterflies fly out of view at very high altitudes. I am curious if monarchs fly at high altitudes too?

Susan: Monarchs can fly high. If you have ever watched and compared butterflies' flights, you will notice that most butterflies flutter their wings. But the monarch flaps and glides. So that's a distinctive flight pattern of the monarch, which allows it to get to higher altitudes where it can catch wind currents to help it travel further.

Ayesha: What is the total number of miles they cover during their migration?

Susan: We can only calculate the distance based on where a butterfly was tagged and where it ended up in Mexico. That's the only scientific data we have. It is highly unlikely that a butterfly that was tagged on its way to Mexico will be found on its migration north come spring. But since we know that the generation that flies to Mexico has to fly at least part of the way back, some butterflies fly between 2500 -3000 miles. That is the whole idea of migration versus immigration. Immigration is one way, and migration is two-way.

Ayesha: So one little butterfly with a wingspan of 4-5 inches can fly up to 3,000 miles?

Susan: Yes, it can be that far.

Ayesha: Do we know how many miles they cover in a day?

Susan: They travel about 25 to 30 miles per day unless they catch the tailwind. One butterfly was documented to have traveled 265 miles. The reason we know that is because it was tagged, and then it was found the same day further south in the United States. The person captured the butterfly, read the tag, and estimated the distance. It was interesting because there aren't that many recoveries of tags within the United States. Most of the recoveries are down in Mexico.

Ayesha: Why aren't tags recovered in the United States? Do the butterflies not come down to forage?

Susan: Yes, they come down to nectar. It's incredibly important that the butterflies have enough nectar sources on their migration route. Unlike the hummingbirds that lose weight, the monarch must gain weight on their migration south to build up enough fat reserves to last all winter in Mexico. So, they need to nectar on their migration.

The reason fewer tags are recovered in the United States is that only about 100,000 butterflies are tagged each year, but millions of butterflies travel to Mexico across the eastern United States. What are the chances of finding one in such a large area? However, since all of them overwinter in a few hectares in Mexico, the probability of finding one that is tagged increases significantly.

Ayesha: Are there any specific conditions under which the butterflies don't fly?

Susan: Butterflies don't fly at night, when it's raining, or when there are strong winds. They find shelter under these conditions. 2

Conservation

Ayesha: What are some of the threats that monarch’s face as a species?

Susan: Habitat loss in the breeding area here in the United States because of humans. We have urban sprawls and commercial developments. We are expanding our agricultural footprint and farming only monoculture GMO crops. It is a problem, especially in the Midwest, where corn and soy have been genetically modified to be unaffected by Roundup. But Roundup kills the milkweed and pollinator plants, which make up their breeding habitat.

Loss of habitat in the overwintering area in Mexico. Their overwintering grounds are not in or around sprawling cities but remote areas. However, these areas are accessible to illegal logging. In recent years trees are also being lost to bark beetle infestation, which was not a widespread problem. But the drought in 2009 weakened almost 9,000 firs which allowed the beetles to destroy the bark and bore deeper and damaged them. To control the infestation, the trees must be cut and cleared methodically, so the beetles don't spread to other trees. Losing trees to illegal logging or bark beetle infestation opens up the canopy, allowing the butterflies to get wet and cold, which is more deadly.

Overuse and misuse of pesticides in the United States are harmful to butterflies.

Climate change is another threat. The monarch depends on three countries. What if the climate changes in a way that the mountains in the overwintering grounds in Mexico do not provide the microclimate the butterflies need? Where are they going to go? The hurricanes and the storms are getting more intense now with climate change. These intense weather conditions would disrupt their flight patterns. What if there is so much drought when the butterflies come through that they can't find nectar plants? Or it's too warm, and their life cycle is sped up, putting them out of sync with the plants? Climate change has so many unknowns.

Unregulated tourism is an issue. Dust caused by horseback riding too close to the colonies disturbs the colonies. Speaking too loudly or making noise disturbs the butterflies and makes them fly, expending their resources. One needs to be very quiet when visiting the colonies; you can't get too close to the butterflies as carbon dioxide from our breath can disturb them.

The wildfires in California are impacting the western population. All those fires destroyed their habitat, and the air pollution affected them. In 2020, the Monarch numbers in the western population were as low as only 2,000 butterflies in the over-wintering grounds.

Finally, we have vehicle collisions, natural predators, diseases, and invasive species.

Susan: Habitat loss in the breeding area here in the United States because of humans. We have urban sprawls and commercial developments. We are expanding our agricultural footprint and farming only monoculture GMO crops. It is a problem, especially in the Midwest, where corn and soy have been genetically modified to be unaffected by Roundup. But Roundup kills the milkweed and pollinator plants, which make up their breeding habitat.

Loss of habitat in the overwintering area in Mexico. Their overwintering grounds are not in or around sprawling cities but remote areas. However, these areas are accessible to illegal logging. In recent years trees are also being lost to bark beetle infestation, which was not a widespread problem. But the drought in 2009 weakened almost 9,000 firs which allowed the beetles to destroy the bark and bore deeper and damaged them. To control the infestation, the trees must be cut and cleared methodically, so the beetles don't spread to other trees. Losing trees to illegal logging or bark beetle infestation opens up the canopy, allowing the butterflies to get wet and cold, which is more deadly.

Overuse and misuse of pesticides in the United States are harmful to butterflies.

Climate change is another threat. The monarch depends on three countries. What if the climate changes in a way that the mountains in the overwintering grounds in Mexico do not provide the microclimate the butterflies need? Where are they going to go? The hurricanes and the storms are getting more intense now with climate change. These intense weather conditions would disrupt their flight patterns. What if there is so much drought when the butterflies come through that they can't find nectar plants? Or it's too warm, and their life cycle is sped up, putting them out of sync with the plants? Climate change has so many unknowns.

Unregulated tourism is an issue. Dust caused by horseback riding too close to the colonies disturbs the colonies. Speaking too loudly or making noise disturbs the butterflies and makes them fly, expending their resources. One needs to be very quiet when visiting the colonies; you can't get too close to the butterflies as carbon dioxide from our breath can disturb them.

The wildfires in California are impacting the western population. All those fires destroyed their habitat, and the air pollution affected them. In 2020, the Monarch numbers in the western population were as low as only 2,000 butterflies in the over-wintering grounds.

Finally, we have vehicle collisions, natural predators, diseases, and invasive species.

Source: Monarch Joint Venture

Source: Monarch Joint Venture

Ayesha: What were the numbers for the eastern population a decade or two ago compared to where they are now? Is the population stable or declining? If it is declining, what are the new estimates?

Susan: In Mexico, the scientists usually go out in December or January to do the measurements because, at that point, the butterflies are tightly clustered, which gives them a more accurate measurement of the area. But as you can see in this chart, there is a downward trend. In the last five years, scientists have determined that if we want to keep this migrating population intact, we need six hectares of butterflies to exist in Mexico. The reading from 2020 winter is just over two hectares. This is concerning. The numbers are not out for this year. They usually come out in late February.

With every animal population, there is fluctuation from year to year. But these numbers are concerning because they are very low for the population. It's not like the monarchs will go extinct because there are monarchs in other parts of the world. But what we're concerned about is will there be enough to sustain this annual migration.

Susan: In Mexico, the scientists usually go out in December or January to do the measurements because, at that point, the butterflies are tightly clustered, which gives them a more accurate measurement of the area. But as you can see in this chart, there is a downward trend. In the last five years, scientists have determined that if we want to keep this migrating population intact, we need six hectares of butterflies to exist in Mexico. The reading from 2020 winter is just over two hectares. This is concerning. The numbers are not out for this year. They usually come out in late February.

With every animal population, there is fluctuation from year to year. But these numbers are concerning because they are very low for the population. It's not like the monarchs will go extinct because there are monarchs in other parts of the world. But what we're concerned about is will there be enough to sustain this annual migration.

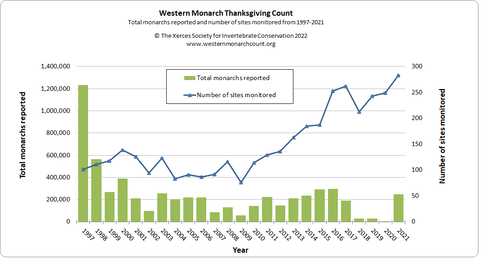

Source: Xerces Society

Source: Xerces Society

Ayesha: What are the numbers for the western population compared to the last two decades? Are they stable or declining?

Susan: The population of western monarch butterflies has declined 99.9% since the 1980s due to various reasons, including habitat loss and degradation, pesticides, and climate change.

The Thanksgiving Count in 2020 recorded the lowest numbers ever for the western population in their overwintering sites. Volunteers counted only 2,000 individuals that year. Although the number of monarchs counted in the winter of 2021 sounds promising at 250,0000 individuals, scientists are cautiously optimistic. Research suggests that the western population may continue to have significant yearly fluctuations; hence, they remain focused on their efforts on conservation.

Susan: The population of western monarch butterflies has declined 99.9% since the 1980s due to various reasons, including habitat loss and degradation, pesticides, and climate change.

The Thanksgiving Count in 2020 recorded the lowest numbers ever for the western population in their overwintering sites. Volunteers counted only 2,000 individuals that year. Although the number of monarchs counted in the winter of 2021 sounds promising at 250,0000 individuals, scientists are cautiously optimistic. Research suggests that the western population may continue to have significant yearly fluctuations; hence, they remain focused on their efforts on conservation.

Ayesha: Are there any statewide or federally funded land restoration projects underway in the United States to improve monarch habitat?

Susan: On April 07th, 2020, the U.S Fish and Wildlife Services and over 40 organizations in the transportation and energy sector signed a Candidate Conservation Agreement with Assurances (CCAA). It’s called Nationwide Candidate Conservation Agreement or Monarch Butterfly on Energy and Transportation Lands. It was signed in preparation for the monarch to be placed on the Endangered Species List. The CCAA agrees to use private lands to increase habitat for the monarchs during migration in the 48 contiguous states. Some of the key elements of the agreement involve growing more nectar and host plants, changing mowing times on vegetation on rights of ways, and collecting data.

On a state level, the Georgia Department of Transportation (GA DOT) partnered with the Georgia Association of Conservation District (GACD) to add 15 pollinator gardens across the state. Ten of these gardens are in the coastal plains, and 5 of them are in the piedmont and mountain regions. These pollinator gardens are slated to be installed at welcome stations and rest areas. They will have signage and educational information to raise awareness about bees, butterflies, and other insect pollinators.

Ayesha: In 2016 President Obama signed a Presidential Memorandum to use federal land to increase pollinator habitat. Was that a mandate or a suggestion?

Susan: It was more of a suggestion. There was federal money put forth for that. Most of the federal lands involved in this initiative are in the Midwest. If you look at the migration map, there is a central corridor that the monarchs use called the I 35 corridor. Georgia is not part of that. We're on the coastal corridor. The monarchs coming through Georgia travel the coastline, for the most part, whereas the rest of the butterflies just come down the center of the country. Fewer of our monarchs make it to Mexico because they have a longer way to go. It's not to say that northeastern and southeastern butterflies don't make it; some do. But the majority of those that make it to Mexico travel through the Midwest, which is the largest breeding area. Georgia should not be dismissed because if we weren't providing nectar and milkweed in the spring and the fall, monarchs would not be able to migrate through or breed in our area.

Ayesha: What can individual citizens do to help the monarchs?

Susan: Planting habitat for monarchs is the number one thing people can do in their gardens to help the monarchs. Each little piece of habitat in individual yards creates a nectar corridor for all pollinators.

University Of Georgia: What can you plant in your garden to help monarchs? Fragmentation of habitat is as much a concern as loss of habitat. I have just one pollinator-friendly garden in my neighborhood. I don’t use pesticides, herbicides, or spray for mosquitos. However, if my neighbors are using all these chemicals and spraying for mosquitoes, it is killing or disorienting bees, butterflies, and other pollinators not only in their yard but mine.

I would say share what you know and raise awareness. Sometimes people don’t know that planting native flowers or milkweed can help Monarch. And, of course, learn more.

Contribute to a citizen science project. There are lots out there. Journey North is a citizen science website where you can report your sightings of monarchs. You can tag monarchs in the fall. You can contribute to the research that UGA is doing on monarch health. When you’re helping the monarchs, you’re helping all the pollinators. The Monarch is just a flagship species.

Other projects are not necessarily Monarch specific, but they are plant or pollinator projects.

There is Bumblebee Watch. There is a phenology project done by the National Phenology Network that helps us understand the blooming time and how it’s sequencing in with the arrival of the migrating species. Pollinator Partnership has one on nectar corridors, which is also about bloom time. It provides information on what’s available in what region and at what time. Citizen science projects help scientists in their research. These projects allow scientists to collect large volumes of data without physically being at these locations.

Ayesha: What is the role of Monarchs Across Georgia (MAG) in Georgia?

Susan: Most of our work is done through teacher workshops, allowing us to reach more students. We have a few partnerships with schools where we do presentations directly for students. For example, we do presentations about the difference between host and nectar plants. We help students learn that a monarch's habitat provides food, water, shelter, and a place for them to raise their young. And finally, how to incorporate all these aspects in their school or home garden.

We do a lot of presentations for Master Gardeners and Garden Clubs.

We have a pollinator habitat certification program that outlines things people can do to get certified. It is a very comprehensive plan. We have a checklist that people can follow to incorporate all the elements that the habitat should have. To be certified, we require that a garden have at least two milkweed species and a minimum of two plants per species. Since we promote habitats for all pollinators, we need people to have host plants for other butterfly species and nesting areas for native bees. You can get more information by going to the Monarch Across Georgia website.

Susan: On April 07th, 2020, the U.S Fish and Wildlife Services and over 40 organizations in the transportation and energy sector signed a Candidate Conservation Agreement with Assurances (CCAA). It’s called Nationwide Candidate Conservation Agreement or Monarch Butterfly on Energy and Transportation Lands. It was signed in preparation for the monarch to be placed on the Endangered Species List. The CCAA agrees to use private lands to increase habitat for the monarchs during migration in the 48 contiguous states. Some of the key elements of the agreement involve growing more nectar and host plants, changing mowing times on vegetation on rights of ways, and collecting data.

On a state level, the Georgia Department of Transportation (GA DOT) partnered with the Georgia Association of Conservation District (GACD) to add 15 pollinator gardens across the state. Ten of these gardens are in the coastal plains, and 5 of them are in the piedmont and mountain regions. These pollinator gardens are slated to be installed at welcome stations and rest areas. They will have signage and educational information to raise awareness about bees, butterflies, and other insect pollinators.

Ayesha: In 2016 President Obama signed a Presidential Memorandum to use federal land to increase pollinator habitat. Was that a mandate or a suggestion?

Susan: It was more of a suggestion. There was federal money put forth for that. Most of the federal lands involved in this initiative are in the Midwest. If you look at the migration map, there is a central corridor that the monarchs use called the I 35 corridor. Georgia is not part of that. We're on the coastal corridor. The monarchs coming through Georgia travel the coastline, for the most part, whereas the rest of the butterflies just come down the center of the country. Fewer of our monarchs make it to Mexico because they have a longer way to go. It's not to say that northeastern and southeastern butterflies don't make it; some do. But the majority of those that make it to Mexico travel through the Midwest, which is the largest breeding area. Georgia should not be dismissed because if we weren't providing nectar and milkweed in the spring and the fall, monarchs would not be able to migrate through or breed in our area.

Ayesha: What can individual citizens do to help the monarchs?

Susan: Planting habitat for monarchs is the number one thing people can do in their gardens to help the monarchs. Each little piece of habitat in individual yards creates a nectar corridor for all pollinators.

University Of Georgia: What can you plant in your garden to help monarchs? Fragmentation of habitat is as much a concern as loss of habitat. I have just one pollinator-friendly garden in my neighborhood. I don’t use pesticides, herbicides, or spray for mosquitos. However, if my neighbors are using all these chemicals and spraying for mosquitoes, it is killing or disorienting bees, butterflies, and other pollinators not only in their yard but mine.

I would say share what you know and raise awareness. Sometimes people don’t know that planting native flowers or milkweed can help Monarch. And, of course, learn more.

Contribute to a citizen science project. There are lots out there. Journey North is a citizen science website where you can report your sightings of monarchs. You can tag monarchs in the fall. You can contribute to the research that UGA is doing on monarch health. When you’re helping the monarchs, you’re helping all the pollinators. The Monarch is just a flagship species.

Other projects are not necessarily Monarch specific, but they are plant or pollinator projects.

There is Bumblebee Watch. There is a phenology project done by the National Phenology Network that helps us understand the blooming time and how it’s sequencing in with the arrival of the migrating species. Pollinator Partnership has one on nectar corridors, which is also about bloom time. It provides information on what’s available in what region and at what time. Citizen science projects help scientists in their research. These projects allow scientists to collect large volumes of data without physically being at these locations.

Ayesha: What is the role of Monarchs Across Georgia (MAG) in Georgia?

Susan: Most of our work is done through teacher workshops, allowing us to reach more students. We have a few partnerships with schools where we do presentations directly for students. For example, we do presentations about the difference between host and nectar plants. We help students learn that a monarch's habitat provides food, water, shelter, and a place for them to raise their young. And finally, how to incorporate all these aspects in their school or home garden.

We do a lot of presentations for Master Gardeners and Garden Clubs.

We have a pollinator habitat certification program that outlines things people can do to get certified. It is a very comprehensive plan. We have a checklist that people can follow to incorporate all the elements that the habitat should have. To be certified, we require that a garden have at least two milkweed species and a minimum of two plants per species. Since we promote habitats for all pollinators, we need people to have host plants for other butterfly species and nesting areas for native bees. You can get more information by going to the Monarch Across Georgia website.

Who to Support: Please find listed below organizations that are working to protect the monarch butterfly and other species of invertebrates. Follow their links to learn more about their work and the species they protect. Please consider supporting their cause by making a donation, signing petitions, volunteering, learning about their work and educating others.

Monarchs Across Georgia/ Environmental Education Alliance

Xerces Society

Journey North

World Wildlife Fund

Monarch Joint Venture

The National Wildlife Federation

Monarch Watch

Project Monarch Health

Monarchs Across Georgia/ Environmental Education Alliance

Xerces Society

Journey North

World Wildlife Fund

Monarch Joint Venture

The National Wildlife Federation

Monarch Watch

Project Monarch Health